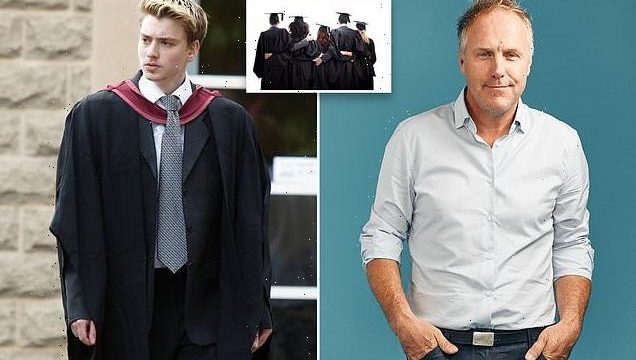

As Tony Blair’s son Euan questions the value of a degree, SIMON MILLS issues a heartfelt riposte and reveals… ‘My lifelong shame over failing to go to university’

- Tony Blair’s eldest child Euan, 38, has been lobbying the Government to consider scrapping exams and university degrees for many people

- Euan suggests that ‘an obsession with academic as a marker of potential and talent’ is actually holding people back in the modern age

- UK-based journalist Simon Mills counters this admitting he wanted to go to uni

So, Tony Blair’s eldest child, Euan Blair, now 38 years old and proud owner of a £22 million London townhouse (two-storey ‘iceberg’ basement, indoor pool, gym and multi-car garage) and a business worth over £700million, wants us to know that going to university is not the only way to become rich and successful.

Even though he did actually go to university himself — ‘not really enjoying studying’ at Bristol and Yale — and then became really, really rich, setting up the Multiverse training provider business after leaving his first job at the investment bank Morgan Stanley.

More recently, Blair junior has been lobbying the Government to consider scrapping exams and university degrees for many people, suggesting that bodies like his own apprenticeship programme (did I mention Euan went to university in England and attended the best university in the U.S.?) would provide a better way into a lucrative and useful career.

Despite Blair’s Oxford-educated Prime Minister father’s three priorities back in 1997 being ‘education, education, education’, Euan still isn’t convinced.

Tony Blair’s eldest child Euan, 38, (pictured) has been lobbying the Government to consider scrapping exams and university degrees for many people. Euan suggests that ‘an obsession with academic as a marker of potential and talent’ is actually holding people back in the modern age

‘An obsession with the academic as a marker of potential and talent’ holds back people from minority groups and fails to serve the needs of employers in a digital age. Work for Google or Facebook, go for a tech start-up, get into coding or join a hedge fund, reckons Blair, and your Classics degree isn’t going to help you.

As a higher-education refusenik, still gainfully employed, I’m not so sure. I share a lack of college education with the likes of Alan Sugar, Simon Cowell, Karren Brady and Richard Branson, all of whom went straight from the school desk to shop floor and then got very rich. The only difference between me and Lord Sugar being somewhere around £1.21billion.

Yes, I know that Bill Gates and Mark Zuckerberg, worth $125billion and $71.5billion respectively, were both college drop-outs, but now, some 40 years after leaving school, I harbour profound shame and regret at my pathetic lack of ambition and a feeling I disappointed parents who worked so hard to get me there.

After I left school at 16, my mum kindly suggested it would be quite funny if I had one of these IDONTGOTO UNIVERSITY sweatshirts. I laughed it off and never let on that, inside, my failure to achieve was killing me. But would I have done any better if I had graduated… or at least turned up and got a genuine university T-shirt?

UK-based journalist Simon Mills (pictured) counters Euan’s argument, admitting that he wishes he had gone to university

I attended a public school in Hull, but being disruptive and lazy, was asked not to come back after my O-levels, of which I achieved six. Pretty crumby grades in four of them, but straight As in English Language and English Literature.

Humiliated in front of a teacher panel, I cried at the gates but quickly took advantage of the sudden opportunity. With two friends, I left Yorkshire for the south of France and spent an idyllic long summer as a deckhand on a luxury yacht in Antibes. Now my eyes were open. I was 17 and I wanted much more of this.

Back in Yorkshire I attended a state college and got three A-levels. Again, an A in English Literature. Mostly to appease my parents, I half-heartedly applied for a few universities but didn’t really see it through.

Actually, I was devastated not to be going. My friends were living it up in gothic and corduroy-ish places such as Edinburgh and Oxford. I wanted to be there too, reading English literature and dressing like Sebastian Flyte in Brideshead. But the word ‘student’ was actually a pejorative term back in the 1980s, when squares from university were thought to be ruining everything just by their tweedy collegiate and therefore privileged presence.

So I took the easy way out and didn’t go, styling out my non-attendance by telling people I wanted to get straight to work (I didn’t really).

Anyway, the moment was gone. My friends all had a year’s head start on me. So after some profoundly undignified messing around and claiming unemployment benefits for six months, I did a Dick Whittington; packed my bags, hitchhiked to London and decided to become a journalist. With A-levels like mine, how difficult could it be? Behind the till in a series of shops to get some money in my pocket, I applied by handwritten letter to the magazines I wanted to work for.

Euan Blair suggests that academia acts as a marker of potential talent and that this should be changed

Nothing. So I tried another route. Finding their addresses, I simply strolled up to the front door and rang the bell, asking each receptionist if I could talk to the editor. Incredibly, they all said ‘yes’, perhaps impressed more by my audacity than my journalistic experience… of which I had none.

By the age of 21, it was now me who had a head start on my friends. They were doing their finals — I was writing for magazines like The Face and i-D. By 22 I’d added the popular Smash Hits and Just Seventeen to my roster, regularly travelling to New York and Los Angeles to do interviews. At 25 I was made editor-in-chief of a successful teen glossy and at 27 I was the deputy editor of a Sunday broadsheet newspaper’s colour supplement.

But I couldn’t help noticing that all around me, wherever I worked, were smart, nonchalantly bookish people with degrees, spouting informed political opinions and myriad literary references.

At the newspaper, pretty much everyone had been to Oxford or Cambridge. Even the Smash Hits editor, whose job was dealing with silly articles on Blue Mercedes and Strawberry Switchblade, had been at Oxford with one Tony Blair.

I was painfully aware of always being the least educated person in the room. Somehow, I got away with it. ‘Where did I go? School of Hard Knocks, then the University of Life. Graduated with honours,’ I’d say if anyone asked.

To this day, people still ask that question. And still, the shame lingers. Among my friends, we are split 50/50 in terms of people who did and who didn’t go to university. The ‘non-Us’ tend to work in fashion, design, music, as property dealers and entrepreneurs. The graduates are bankers, lawyers and doctors. They are all a lot richer than me.

Not that I am more than a little besotted with everyone else’s success, of course. Then again, maybe Euan Blair is right and that 40-something years on, perhaps my own ‘obsession with the academic as a marker of potential and talent’ is still holding me back…

Source: Read Full Article