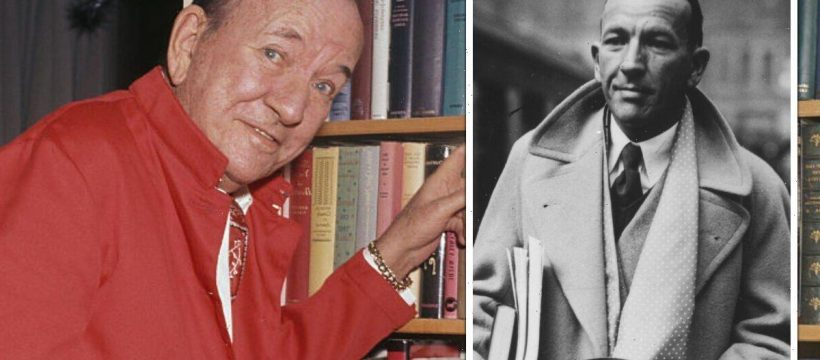

In his time he was the most famous Englishman in the world, feted across seven continents for his songs, plays and films. Witty and urbane, equally at home with royalty and the man in the street, he was a stage and screen idol like no other. Best known to later generations for his part as gangland boss Mr Bridger in Michael Caine’s The Italian Job, Noel Coward was, between the wars, the most important star to come out of Britain.

His writing output was astonishing, and with his plays he made stars out of generations of actors. Private Lives, originally staged in 1930, promoted later talent as varied as Downton’s Maggie Smith, Hollywood’s Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton, and the infamous Tallulah Bankhead, while Blithe Spirit remains a classic.

Even today, almost every minute of every day, somewhere around the world, a Noel Coward play is being produced.

It seems impossible, then, that a man with such a huge global profile could become a spy. But he did.

In the summer of 1938 Coward, now as famous on Broadway as he was in London’s West End, travelled to Italy where he witnessed the Fascist regime of Mussolini. It triggered a hatred for Fascism and a determination to do his bit in the impending conflict.

“He wished to contribute to a second war… in such a way that he would once and for all be taken seriously as a public figure,” writes Oliver Soden in his revealing new biography of the man who came to be known as The Master.

“This was a final renunciation of the Bright Young Things, and a chance to have a crack at the heroism instilled in him in childhood, when he once acted the part of a little boy who saved the world from war.”

As he travelled through Italy and other countries that summer, Coward was sending back secret reports to Robert Vansittart, a man described as chief diplomatic adviser to His Majesty’s Government but in fact Whitehall’s spymaster.

With no funds forthcoming from a slumbering Treasury, Vansittart still managed to build a private “detective agency” collecting intelligence on German rearmament with the aim of destroying the arguments for appeasement.

“He formed a secret nexus of bankers and industrialists who were rich enough to pay their own expenses,” writes Soden in Masquerade: The Lives Of Noel Coward. And now at the height of his fame, Coward had enough cash to join the party.

That autumn he was sent by Vansittart to Switzerland to assess whether its government was swallowing Nazi propaganda: nobody knew whether the Swiss would side with the enemy if war was declared.

“I snooped around a good deal,” Coward reported back, and such was the success of his mission that, a few months later, he was on his travels again – to Poland, Russia, and Scandinavia, all countries vulnerable to German attack.

Summoning newspaper reporters to his home, he made very public his intention of visiting these places. “[He was] calling the bluff of those who [suspected] him of spying, by pushing to its absolute limits the notion of hiding in plain sight,” writes Soden.

In Danzig – at that time a “free city” established by the League of Nations – he walked streets thronged with German soldiers (even though the Nazi invasion was still months away) to deliver a secret letter to the League of Nations commissioner who was about to meet Hitler.

Then this “spy in plain sight” took a 1,200-mile train journey to Moscow. The British government still had no idea which way Russia would jump in the event of war, and Vansittart was in desperate need of information on the state of German-Soviet negotiations.

Coward travelled to Leningrad, staying in the bugged rooms of gone-to-seed hotels, and writing home: “The Russians opened everything, and turned out all my clothes. What they hoped to find I don’t know – I kept any papers of importance in my hip pocket!”

When WAR finally broke out, Coward was given a government propaganda job in Paris, though first he was sent to be briefed at “the Riding School Organisation” – a hush-hush operation hiding behind layers of barbed wire at a mansion near Bletchley Park.

Once in France – not yet invaded – his job was to cosy up to his French opposite number. But liaising with his own side proved more difficult.

“Nobody seemed to know the code words he’d so carefully learned to avoid detection on the tapped phone lines,” writes Soden.

As with his stage performances, he’d polished his act as a spy and was infuriated at the amateurism of others. Coward moved into a flat near the Paris Ritz – “no hot water, but a Steinway grand piano” – and was given an armed guard.

Maybe he thought he’d reached the zenith of his spying activities when he was given the job of hosting visiting dignitaries including the former King Edward VIII, now Duke of Windsor. Even so, he may still have been sending reports back to Vansittart on the ex-king who was suspected – then as now – of nursing a private admiration for Hitler.

“I have a lot of very secret information and am doing a very important job for my country,” he wrote to his mother, perhaps overselling the goods.

But he always applied the same level of professionalism as he did to his stage performances – an intelligence officer described Coward giving dinners at his flat “for guests of every kind: artists, journalists, painters, writers. This was real propaganda of skill, a valuable source of information”.

One real piece of cloak-and-dagger work he undertook was to recruit Otto Katz, apparently working in French propaganda but secretly a Soviet spy, to become a double agent. When Katz was put on trial after the war, Coward was named by him as holding “an important position in British Intelligence – he appealed to me to join him, and I pledged myself to work for the British Intelligence service”.

Coward took time out to join the fabled French singer Maurice Chevalier entertaining the troops who were defending the doomed Maginot Line, but after six months in France he was beginning to feel the pointlessness of his job. One scheme cooked up to demoralise the Germans was to drop carrier pigeons with propaganda messages tied to their legs.

The five birds who bothered to fly home were found to be carrying rude replies in German.

So instead, Coward was sent to America, where his name carried more weight, and arguably he could do more towards the war effort.

The American President, Franklin D Roosevelt, had promised the USA would remain neutral and 90 per cent of the population, in 1940, agreed with that position.

Coward made his way to Washington and quickly organised himself a place on influential guest lists where he could talk to politicians and journalists, hoping to shift US public opinion through them. Soon he was dining with Roosevelt and his wife, though the politician was wedded (and would remain so until Pearl Harbor) to a foreign policy which would keep all sides happy.

Coward was determined to use his fame to shift American opinion, and gathered together a list of lawyers and journalists who were broadly sympathetic and who could be utilised by the British government at a later date. He also saw the publicity value of getting British actors still working in Hollywood – like David Niven – to publicly return home and take their place in the war machine.

He was invited back to the White House and spent time alone with the President. Next morning, he reported: “Sat on the President’s bed and talked, mostly about the Italian situation.”

So intimate a meeting would not be accorded to Winston Churchill or King George VI when they travelled to the US – which just demonstrates that while Coward’s activities as a spy may not have done so very much to win the war, his involvement with the spy community produced other, more lasting results. Coward carried back to London a personal message which he delivered over a lengthy dinner with Winston Churchill, now installed as Prime Minister.

One last attempt to turn him into a fully-fledged spy ended in failure – he was to be sent to South Africa and Venezuela under the cover of being a British Council lecturer, but with the purpose of filtering back intelligence.

He was taught how to use a pistol and looked forward to this exciting development in his secret life. But enemies in high places saw him off – “Sick to death of this rot,” he fumed. “Bitterly disappointed in Winston and the whole lot. God damn them – stinking, self-seeking political rats!”

And so for the rest of the war Noel Coward went back to what he did best, utilising his famous talent to amuse. His days of hiding in plain sight were over – it was time to return to the limelight.

● Masquerade: The Lives Of Noel Coward by Oliver Soden (W&N, £30) is published on Tuesday. For free UK P&P, visit expressbookshop.com or call 020 3176 3832

Source: Read Full Article