Jill Fairchild — who in her quiet way was as much of a force, and had as much of an impact, as her late husband John B. Fairchild, WWD’s legendary editorial director and publisher — died June 25 at age 94. They were a couple who perfectly complemented one another and who, at the time of his death in 2015, had been married 64 years.

A slim, beautiful woman for whom the words “elegant” and “erudite” seemed to have been invented, when she walked into a room there was something striking about her quietly understated style and composed presence, even into her late age, that exemplified her father’s and grandfather’s military backgrounds. There was nothing flashy about either her clothes — a mix of famed designer labels and exotic finds — or her homes, which over the years stretched from New York to Nantucket, London to Gstaad. Yet everything — from the food to the flowers to the furnishings — was always just so in how they were arranged or served.

She was, simply, a perfectionist, taking delight in both the smallest things as well as the biggest — from the stunning intricacy of a bird’s feather to a breathtaking artwork in the Frick Museum or the Neue Galerie.

While John Fairchild — forever “Johnny” to his wife — would be the one renowned, and feared, for rattling the cages of designers, industry titans, socialites, and more, Jill Fairchild was an equally acute observer of fashion, people, style and culture, and always remained steadfast in her judgments. There is no saying more apt to their relationship than that of “behind every successful man stands a woman,” as she invariably, and quietly, encouraged him — advising, suggesting story ideas for WWD and especially W and bringing her European sense of style and wry English humor to broaden his preppy, WASP-y upbringing.

Related Gallery

All the Looks at the 2021 Cannes Film Festival

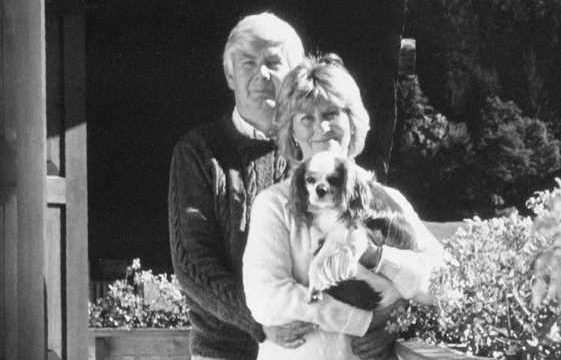

Jill Fairchild Courtesy Photo

The only child of Longin L. Lipsky — who was born in Perm, Russia, and fled to Britain during World War I and joined the Royal Air Force — and the former Helen McFarlane, who was born in Cork, Ireland, Jill Lipsky was born in England and went to boarding school there before her mother remarried, to Jack S. Peliks, and moved to Rio, where she sent her daughter to the Lycee and the American School.

Jill Lipsky met John Fairchild in Paris. He was attending Princeton — fresh back from his military service in post-World War II — and she was at Vassar, a transcontinental woman who spoke Portuguese and French. She always recalled that her three-day flight from Brazil to New York to start Vassar was the first time she’d ever visited America — and even after over seven decades of living in the U.S. she still had the air more of a European than an American.

They wed in 1950 and shortly thereafter moved to Detroit, where he took a job in the research department of the J.L. Hudson department store chain. But barely a year later they were back in New York and he was working in the family company, Fairchild Publications, as a reporter for WWD. In 1955, John Fairchild was sent to Paris to oversee all of the European coverage for the company’s publications.

The couple would only spend five years in Paris but it was a time they both would always look back upon as among the happiest of their lives and that would turn them into lifelong Francophiles. Paris was still recovering from World War II even a decade after its end, and their life was far from luxurious. They by that time had two children and at one point they lived in a house that had no refrigerator, coal heat and no hot water (it had to be heated on the stove). But the people they met — from Pierre Cardin to the young Yves Saint Laurent and Pierre Bergé, Kim d’Estainville and Andre Oliver, the d’Ornanos of Jean-Louis Scherrer and Marc Bohan of Dior — would remain longtime friends.

Returning to the States in 1960 so John Fairchild could save what was then a struggling Women’s Wear Daily, they remained firmly lowkey. She was almost the antithesis of his world: A shy woman, she rarely appeared at fashion events — in fact, she never went to fashion shows, had no real interest in designer gossip and explained that she couldn’t show any favoritism even to designers who became friends, including Bill Blass and Oscar de la Renta. By then the couple had two more children, and she is survived by them all: John, of Easthampton, N.Y.; James, of Naples, Fla.; Stephen, creative director of jewelry brand Pandora who resides in Brussels, and Jill, founder of accessories brand Fairchild Baldwin who resides in New York — as well as eight grandchildren — Jessika, James, John, Alexa and Natasha Fairchild and Peter, Elizabeth and Reed Melhado.

And while their circle over the years included social beings such as the late Brooke Astor, and Susan and John Gutfreund, more of their friends were writers or artists than designers or socials, including Sir Stephen and Natasha Spender and later their daughter Lizzie Spender and her husband Barry Humphries; the writer and decorator Rory Cameron; garden designer Madison Cox; Jean Lafont, who was called “the king of the Camargue;” Freddie and Isabel Eberstadt, and the decorator Lady Vivian Greenock.

Jill Fairchild Courtesy Photo

Their friends exemplified what was a defining characteristic of them both — an endless curiosity. It was what led her to develop several different careers during her life. She made documentaries; wrote a book, “Trees: A Celebration,” one of the subjects she was most passionate about; the book “Letters from the Desert,” which included a collection of responses to letters she wrote to troops serving in the first Gulf War — and which drew praise from the likes of Ronald Reagan, Colin Powell, Norman Schwarzkopf, Barbara Bush and Lady Bird Johnson, and also wrote numerous articles for W when it was part of Fairchild Publications.

Their breadth showed her varied interests, ranging from interviews with astronauts and writers to travel articles on Big Sur, a recounting of a hilariously disastrous trip down the Nile when their boat got stuck for days, and one on their trip to China with Bill Blass shortly after the country reopened to the West. Most of the stories she wrote also carried her photographs, a passion as she would shoot away with her trusty Leica.

Another passion was drawing — she learned to sketch with colored pencils, and would draw gallery-worthy pictures of botanicals, from sunflowers to sprays of lavender, irises to roses.

There was almost nothing she wasn’t curious about: Art (she created her own “museum” by putting postcards she collected from art museums over the course of four decades into photo albums and would spend hours arranging and rearranging them until she felt the pages were finally perfect); music (she loved the sonatas of Mozart, and even into late age would listen to them on an aged Sony Discman), and Nature in all its majesty and mystery, from the fireflies in the summer in the Hamptons to, above all, birds. A robin that surprisingly laid eggs on her balcony transfixed and mystified her for weeks, while in her later years she became passionate about the Audubon Mural Project in Manhattan’s Harlem. Her enthusiasm led her to tap Gail Albert Halaban to photograph some of the paintings before they disappeared, and the photos were subsequently displayed at an exhibition at the Aperture gallery.

“I thought there should be an artistic and documentary record of the murals, and an exhibition, because these murals are ephemeral, soon damaged by weather or graffiti, and to spread awareness about the project, and the fragility of our bird population,” Fairchild said in the catalogue of the exhibition. “Our lives are enriched by the diverse beauty of birds, and their song. So now, let us celebrate the birds of Harlem.”

Then there were books. A voracious reader, a conversation with her about literature invariably left one feeling uneducated. Memoirs, letters, travel tales, children’s books (she loved “The Wind in the Willows”), poetry (Seamus Heaney was one of her favorites), histories, Shakespeare — she read them all, as well as novel after novel. She howled with laughter over the satire of Evelyn Waugh, especially “Decline and Fall” and the “Sword of Honor Trilogy”; enjoyed E.M. Forster, Graham Greene, and Laurence Durrell, but above all revered the two Russian icons Leo Tolstoy and, even more, Anton Chekhov. To her, the Russians captured L-I-F-E and human nature and she would constantly read and re-read the short stories of Chekhov.

For, in the end, beyond family, nothing was more important to her than appreciating the smallest things in life — from the blue of the sky to the shape of clouds, the magic of trees and flowers, or the tiniest seashell. Her face would glow talking about sightings of snowy owls on Nantucket, the wildflowers covering the hills near Gstaad, or the beauty of the gardens of Paris — and she always encouraged her family and friends to use all of their five senses to truly see things in all their majesty.

To her, Nature represented the circle of life. As her grandson Peter Melhado wrote following his grandmother’s death: “Watching the trees blow or listening to the birds chirp in the summer wind, I feel like maman was content in these moments. She always talked about the circle of life: Dirt becoming trees, trees dying and rotting into dirt and then becoming trees again. A cyclical and interconnected world of Nature that, out of death and sadness, creates something beautiful.”

A private funeral service is being planned. The family has asked that contributions in her memory be made to Doctors Without Borders.

Source: Read Full Article