You’re a young performer who’s suddenly seeing the cash roll in, after years of toil and struggle. Or maybe you’re an experienced director or screenwriter, still smarting over bad choices in spending or investments. As nerve-wracking as maintaining an entertainment career can be, worries about the state of one’s finances must dial the pressure up to 11.

Small wonder it’s the rare creative who doesn’t seek out the help of a financial professional.

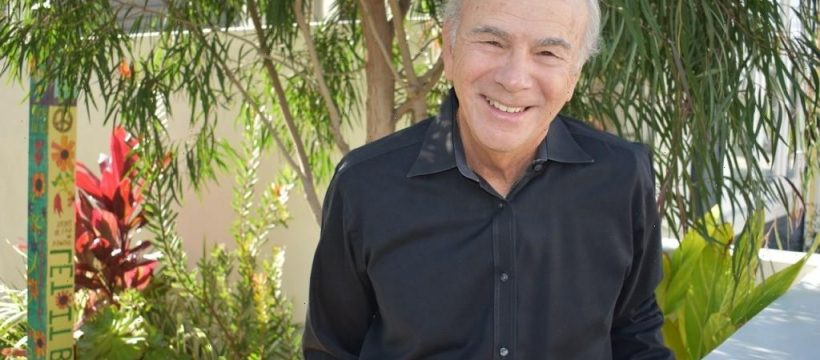

“Under normal circumstances, artists are people who can create beautiful, wonderful things,” asserts Barry Siegel, a senior managing director of Provident Financial Management known for his starry client list and impressive performance. “But they really don’t have the time, or the inclination, or the ability to deal with the more businesslike functions of our society.”

Translation: The business manager is an essential component of any well-run artistic career. Personal managers and attorneys can sort out available options, and agents can cut deals. But when it comes to money management, there’s no substitute for a skilled professional who can assess one’s financial situation, advise on life-changing decisions and plan for an advantageous future.

Just ask longtime Siegel client Al Pacino. “I just feel freer to go out and do what I do, because I have an honest person working my finances,” he explains. “I don’t have to look over my shoulder, and that’s a big plus in this world.”

An exceptional business manager does much more than get the bills paid. “If there’s a contract for a film or TV show,” says Siegel, “it’s our job to make sure that that money comes in when it’s supposed to, and to pursue that cash if it doesn’t.” A firm will advise on major purchases, from homes to airplanes. It can advise on the client’s charitable giving and, of course, help with estate planning.

Artistic legacies are also at stake. “Every artist believes that their music will live on forever,” Siegel reminds us. “But the reality of life is that most artists don’t go on forever.” Wise business management can extend the shelf life of a body of work beyond the creator’s lifetime.

Des McAnuff, original director of “Jersey Boys,” calls Siegel “a font of wisdom. He’s really been our sage,” he says, citing Siegel’s deep love for the arts that complements financial acumen. “Having him at our side during this crisis, with all our shows shut down, has been a godsend.”

With so much at stake, handing over control of one’s affairs is not to be undertaken lightly. McAnuff recommends extensive research into a manager’s track record, in search of “forthrightness and honesty.” (On that score, he adds, “Barry gets nothing but gold stars, so that was painless.” For his part, Pacino was sold because, “Barry exudes confidence. He does it without even trying. I appreciate that.”)

Siegel suggests that a prospective client carefully assess the relationship between a management firm and its bank. At its inception in 1982, Provident began an association with City National Bank that continues to this day. “City National has been the most supportive of us as a firm, and of our clients in their specific needs. I think their entertainment division is the best in the industry,” he asserts, pointing to the banking team’s deep knowledge of artists’ situations, and its extensive experience in funding massive tours and other large startup endeavors.

“I would love to say that it was us that did everything and that we’re the best,” Siegel says, chuckling. “But without City National Bank’s direct help, we could not be in the position we are. They have taken the time to become human with our clientele and with us. I know I can get someone on the phone whenever I need them.”

Siegel and team conduct what he calls “a good-fit interview” with each potential client. Business management is labor-intensive, with as much as 50% of a firm’s annual gross revenue applicable to labor costs. Therefore, “we need to be very careful about which development artists we bring in. And even on established artists: How much time will they take? We need to make that decision,” he says.

Personal chemistry has an impact, as Siegel is ever mindful of what he calls “our Provident family. If our staff have to deal with someone who is not a nice person on a day-to-day basis, how does it make them feel about their job? How does it make them feel about us?” No matter how glittering the luminary, when an impending arrival at Provident’s Santa Monica office makes staffers blanch, Siegel is blunt: “It’s not worth it. … We’ve resigned [from working with] very large-paying clients that have been rude to our people.”

McAnuff echoes the importance of the personal touch. “You can never have anybody in your life whom you dread talking to.” At the same time, he stresses that clients must take personal responsibility for their own affairs.

“In the arts, we tend to revert to being teenagers. And if you’re doing something that you love, it can take over your time and concentration,” McAnuff says. The temptation to simply turn the purse strings over to a “grownup” can be strong but must be resisted, which means constant awareness of one’s own financial position.

In that vein, Siegel emphasizes that his role is deliberately advisory. “We need to look for the right solution to make the future bright for our client,” yet “we do not make final decisions at all.” He clarifies, “We’re not, ‘Yes, ma’am.’ We will tell the client what we think. But it’s really up to the client to make the final call.”

Which is why, in the final analysis, “an informed client is the best client a business manager can have.”

© 2021 City National Bank. All Rights Reserved.

Source: Read Full Article