On Thursday, two World Health Organization agencies released their findings on aspartame, the artificial sweetener found in thousands of sugar-free products like diet sodas, chewing gums, yogurts and energy drinks.

The organization’s International Agency for Research on Cancer classified aspartame as possibly carcinogenic to humans. A separate group, the Joint Expert Committee on Food Additives, said that there was not convincing evidence of a link between aspartame and cancer in humans and that people could still safely consume the sweetener in moderate amounts.

The announcement does not mean that aspartame definitively causes cancer, W.H.O. experts said in a news conference; instead, it is a call for additional research into its health effects.

The W.H.O. is not advising companies to withdraw products that contain aspartame or urging people to stop consuming it altogether, said Dr. Francesco Branca, director of the Department of Nutrition and Food Safety at the agency. “We’re just advising for a bit of moderation,” he said.

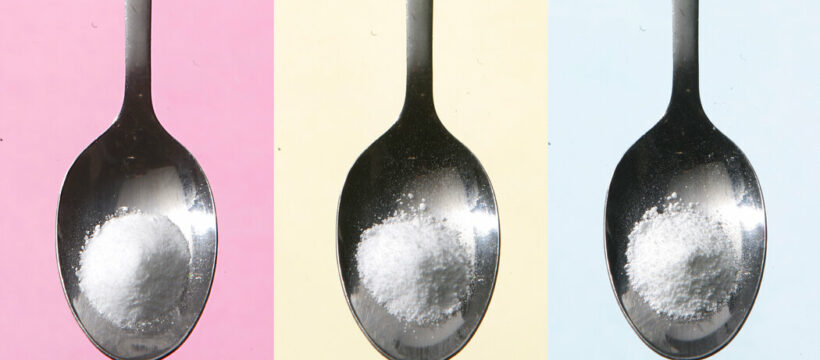

How much aspartame is too much?

According to the W.H.O., it is safe to consume up to 40 milligrams of aspartame per kilogram of body weight per day. Using diet soda as a measure, the limit means that, by some estimates, a 150-pound person would need to drink more than a dozen cans each day to surpass it.

The Food and Drug Administration is slightly more permissive with its daily safety limit. It states that people can have up to 50 milligrams of aspartame per kilogram of body weight each day.

An F.D.A. official said agency scientists did not have concerns about the safety of aspartame when the sweetener is used “under the approved conditions.”

“Aspartame being labeled by I.A.R.C. as ‘possibly carcinogenic to humans’ does not mean that aspartame is actually linked to cancer,” the official wrote.

Given the vast quantities of sweetener under discussion, several experts said that consumers should not necessarily worry about the cancer risk of their aspartame consumption. Reaching that upper daily level of aspartame intake “isn’t casual consumption,” said Dr. Dale Shepard, a medical oncologist at the Cleveland Clinic. “This is making a project out of trying to get aspartame.”

What else does the I.A.R.C. consider a possible carcinogen?

The International Agency for Research on Cancer labeled aspartame as “possibly carcinogenic to humans,” a category that includes more than 300 viruses, chemicals, occupational exposures and more. Certain pickled vegetables, engine exhaust, some types of human papillomavirus and working in dry-cleaning all fall into the same I.A.R.C. category.

The new classification for aspartame is based on limited evidence that has linked the artificial sweetener to liver cancer in humans. There is inadequate evidence to show that it can cause other types of cancer, and experts don’t know exactly how the sweetener might contribute to cancer. The group also found limited evidence that aspartame was associated with cancer in animals.

By contrast, alcoholic beverages fall into the most extreme classification: “carcinogenic to humans.” The I.A.R.C. also classifies air pollution, tobacco and processed meats as carcinogenic to humans.

“The larger challenge is that with aspartame, like other additives, there’s just not enough science to say definitively, ‘Yes, this causes cancer’ or ‘No, it doesn’t,’” said Dr. Dariush Mozaffarian, a cardiologist and professor of nutrition at the Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy at Tufts University.

In terms of lowering cancer risk, people should first think about other factors that may make them more susceptible, like obesity as well as alcohol and cigarette use, said Dr. Neil M. Iyengar, a medical oncologist and physician scientist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City.

What do we know about other sweeteners?

There is an array of artificial sweeteners on the market, with varying chemical structures. Data on their long-term health effects is lacking.

There’s no clear “winner” that is the best for you, said Joanne Slavin, a professor of food science and nutrition at the University of Minnesota-Twin Cities.

In the spring, the W.H.O. said that artificial sweeteners like aspartame, stevia, sucralose and saccharin may not help people lose body fat and that consuming them might be associated with a greater risk of cardiovascular disease, diabetes and overall mortality. Erythritol, a zero-calorie sugar substitute, has recently come under scrutiny for its potential links to cardiovascular issues, although that evidence is inconclusive.

Some health experts recommend phasing out artificial sweeteners from your diet altogether, as challenging as that may be. “If they don’t do any good, and they’re not required in the diet, and there’s no real advantage — why bother with them?” said Marion Nestle, a professor of nutrition, food studies and public health at New York University.

But sugar comes with concerns, too. Anything that consistently spikes your blood sugar can be a problem, especially if you have diabetes or another metabolic disorder. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has linked the frequent consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages, like regular sodas, with Type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, kidney diseases, obesity and other health concerns.

“There’s always risk,” Dr. Slavin said. “In the end, if you can stand the calories, maybe a little bit of sugar in lemonade is better than an alternative sweetener. That’s your call, depending on your health status and what you want to do.”

Dani Blum is a reporter for Well. More about Dani Blum

Source: Read Full Article