The desert will again be a hotbed of deceit and larceny in luxurious black-and-white as the Arthur Lyons Film Noir Festival returns to Palm Springs this Thursday through Sunday, with the quintessential noir classics “The Killing” and “Double Indemnity” bookending a marathon weekend that otherwise tends toward more rarely screened ‘40s and ‘50s titles.

Several sons or daughters of the original actors or directors will be on hand, but of special interest to festival attendees will be the presence of one of the actual filmmakers: James B. Harris, 94, Stanley Kubrick’s producing partner for several of his best early films, who’ll be able to speak first-hand about the making of 1955’s “The Killing,” the crime drama that turned out to be Kubrick’s first real masterpiece.

“I’m just utterly thrilled that ‘The Killing’ will show and Jimmy will be the guest on opening night,” says the festival’s longtime guiding light, author and noted noir expert Alan K. Rode. “The festival’s been around for 23 years, and I’ve been the producer-programmer for the last 18, and I’ve never shown the same film twice. This festival started out showing obscure films of the film noir era, and then I started mixing in the classics. Earlier this year, I was privileged to do the commentary on a 4K edition of ‘The Killing,’ one of the greatest heist films ever made, if not the greatest. Around the same time, a friend introduced me to Jimmy, and it’s been a privilege to get to know Jimmy and hear his vast reservoir of knowledge and insightfulness and honesty about this film and his career, as well as Stanley’s. Having a film like this and having James Harris there is just a win-win for everybody.”

Harris tells Variety that the classification that is now used for crime films of the era never came up during the production of “The Killing,” as any student of the artform will know, since it was only coined by international critics years after the movement had already waned. “No, that term never came up,” the producer says, “but even genre never came up. Noir or genre never entered our minds. It was just a question of taking a good story and turning it into a good film.” In this case, it was Harris showing up with the good story, as he was the one who found the novel “Clean Break” in a bookstore and brought it to Kubrick as the source material for the first of their three seminal collaborations — soon followed by “Paths of Glory” and “Lolita.”

Other guests at the four-day festival at the Palm Springs Cultural Center include David Ladd, who will speak after a screening of his father Alan Ladd’s starring appearance in “This Gun for Hire,” and, following an extremely rare showing of director Josef Von Sternberg’s “The Shanghai Gesture,” a talk with Nicholas Von Sternberg, that filmmaker’s cinematographer son, and singer Victoria Mature, the daughter of one of the movie’s stars, Victor Mature.

Several of the films will be screened in rare 35mm prints, thanks to projectors the Palm Springs Cultural Center (formerly the Camelot Theatre) keeps on hand partly for the purposes of hosting Rode’s noir festival on its big screen every Mother’s Day weekend. Some are provided by studios, but two of the prints come from the Library of Congress and the George Eastman House. (Scroll down for a full lineup of the festival’s offerings, along with times and ticket information.)

In a phone conversation with Rode, Harris talked a bit about the origins and makings of “The Killing,” offering a preview of the dialogue they’ll have during the festival’s opening night Thursday (which will be followed by a party for full passholders).

The film was actually Kubrick’s third directorial effort, but, some would say, the first really good, let alone great, one after “Fear and Desire” and “Killer’s Kiss.” “This was not a money maker for either Jimmy or Stanley, at all,” points out Rode. “And the fact that this got made for a little over $300,000 is remarkable.” Despite its A-level cast and production values, somehow it literally ended up going out as a B-picture, on the back end of double features. Said Harris, “It was disappointing that the film wound up as the second feature to ‘Bandido’… If you’re familiar with distribution, you’ll know that that the second feature usually was just flat rentals, so it would have a limited gross potential.” But there was no limit to how it set Kubrick up to become one of the great directors in the history of cinema.

Harris stresses that the movie’s brilliance is not Kubrick’s alone. The great novelist Jim Thompson was one of the major scripters, although he was relegated to an “additional dialogue” credit, a decision on the director’s part that is one of the few things he slightly knocks his former partner for. And then there was the source novel itself.

“I stress the importance of previously published material. I don’t think enough credit is given to the authors of the books because they did all of the heavy lifting,” Harris said. “Lionel White, in writing ‘Clean Break,’ which became ‘The Killing,’ actually structured the flashback situation, which would show the activity of each participant in the robbery, and so we had to go back to show the beginnings of each participant. That was a pretty courageous thing for us to do, because flashbacks to a great extent were not a popular form of telling a story, we were told.

“Actually when we finished the film, everyone who we screened it for actually suggested that we reedit the picture into a straight-line story because flashbacks would irritate the audience. Because once you bring them to the point where the robbery’s gonna take place and then you flash back to stuff all over again with the different participants, they said the audience is really going to be irate, and you’re gonna have a real problem on the word of mouth. This was something where, if enough people tell you you’re sick, you feel you should lie down. We felt we had to at least go over it again and see: Were we on the wrong track here? Ultimate we figured that, if we’re going to fail, we should fail with our own ideas, not somebody else’s.”

And yet, Harris noted, “We did attempt to reedit the film before we delivered it to United Artists. We rented an editing room and tried to redo it as a straight-line story. And halfway through we looked at each other and said, ‘What on earth are we doing?’ Because the whole reason that we were attracted to the story was the structure that Lionel White had laid out in the book. And so we immediately put it back the way we believe it should be. And as Alan just said, it might be one of the best heist films ever made. So what I’m getting at is that Lionel White, who wrote the book, did all the heavy lifting, even though you could say that we had the good sense to appreciate this and take advantage of it.”

The one significant departure from the novel, plot-wise as Harris recalls it, is the climax. (Very slight spoiler ahead.) “Stanley and I were having dinner one night at the Automat in Times Square, and we were discussing about how we were gonna end the picture. I came up with the idea of: Wouldn’t it be ironic if they go through all this trouble and complete the robbery and at the very end, they get to the airport to take off, and somehow the money all comes loose and blows away? Stanley jumped on this idea because I guess it reminded us of ‘Treasure of the Sierra Madre’ — and so that’s a departure from the book.”

Harris and Rode both discussed what was significant about the noir movement to them, or even how it can be defined. The producer went on an extensive riff, comparing it to the great music of the era.

“I suppose I compare making movies to playing jazz,” said the producer. “Jazz is based on improvisations and variations on the melody. Jazz is an unpopular form of music because it’s too sophisticated for people — because, once the melodic line is stated, then the improvisation takes place and the variations, based on the chords that support the melody, and people lose track of it. Once they lose track of the melody, then they’re lost, and so they don’t appreciate what’s going on.

“Now, I liken making movies to playing jazz, in that you want to dramatize things the way that you see them, and sometimes they don’t hook up directly with the way people see them. People that like popular music, they’re the same people that like movies that have happy endings that are uplifting, so when they come out of the theater, they feel good about things. But some of us like to tell stories the way they really are in life. And that becomes noir, because they don’t always have happy endings, or they have endings that leave you wondering what’s really happening. … The word noir really is something that that got stuck on the kind of films that don’t have happy endings and that deal with the bad side of people, where it forces you to actually root for people who are committing crimes and things. They become the hero of a piece, which is really contradictory to mainstream movies.”

“Crime from the perspective of the criminals,” adds Rode, in a nutshell.

Rode believes noir is the genre or movement of the past that tends to have the greatest attraction for young audiences. “I think film noir is one of the main umbilicals that connects a younger generation with classic film, because the characters and the storylines in a lot of these films deal with the human condition and those things that are so common to noir — and to people — like lust, larceny, greed and betrayal. I think no matter how a younger generation might not understand why doctors smoke cigarettes, and men and women wear funny hats, and the telephones look like the size of boomerangs, it doesn’t matter. They identify with the dialogue, with the story, with the characters. Back when Art (Lyons, the late mystery writer) founded this festival in 2000, his motto was, ‘It’s all in the story,’ and I think that that still holds true.

“And that’s why people continue to come out and see these films the way they were meant to be seen: in a group, in a darkened theater on a big screen,” Rode continues. “So I think maintaining maintaining the viability of the films and the theatrical experience, which is under siege now with streaming, and after COVID, is very, very important. People need to not take it for granted that these films will always be available. Showing film itself has gotten much more challenging, just in terms of the equipment, the qualified projectionists and so forth. It’s much more challenging to be able to present these films as they were intended in a theater than ever before in terms of availability and cost. Every year presents a new challenge, but the thing that’s special about the Arthur Lyons Film Noir Festival is that every year the Palm Springs Cultural Center and myself and the people who support this prove that we’re up to the challenge.”

For fans of noir in Los Angeles who are not able to make it out to Palm Springs, there are other opportunities coming up that involve Rode — even if none of them involve the chance to see as many as five noirs in a single day, as the Lyons Festival does.

First off, for anyone wondering about the fate of Noir City Hollywood, which Rode and Eddie Muller have programmed and co-hosted at the American Cinematheque’s Egyptian Theatre since the 1990s (with a brief post-COVID move to the Hollywood Legion), that festival will return in 2023… just not, as everyone has figured out by now, in its usual April time slot.

“Noir City Hollywood will be coming to the Aero Theater the first week of August,” Rode confirms. “Eddie Muller and I will have a great program along with the American Cinematheque for that, including some live events that we’re working on. We held off for a while because we wanted to see if the Egyptian Theatre would be available. And as it turns out, the refurbishment and the rebuild of the theater (by new owner Netflix) does not look like it’s gonna complete this year, so we’ll be at the Aero.”

Much sooner than that, but also on the west side, Rode is currently involved in the screening of some noirs at the Skirball Center as part of that organization’s ongoing series about the Hollywood blacklist of the ‘50s, running through the end of August.

Meanwhile, Rode’s most recent book, following his acclaimed biography of director Michael Curtiz, is about the film “Blood on the Moon,” which has been described as the ultimate noir-Western hybird — a very specific sub-genre. Rode will be presenting it as part of the festival in Palm Springs this weekend, and signing copies of the book before the screening. But anyone bound to L.A. who’s curious about the film or book can come to a showing and signing at the Autry Museum’s theater in Griffith Park on May 20 at 1 p.m.

Going back to the Arthur Lyons Film Noir Festival this weekend, here’s a Rode-annotated guide to all the vintage films playing, following the Thursday night kickoff at 7 p.m. with Harris and “The Killing.”

Friday, May 12

10 a.m.: “Dial 1119,” directed by Gerald Mayer (1950)

“That’s a 65-minute film produced by MGM and directed by Gerald Mayer, who was Louis B. Mayer’s nephew. This was in the vanguard of message films from MGM’s production chief, Dore Shari, and it’s about an insane murderer who runs amuck while seeking the police psychologist who testified at his trial and takes hostages in a bar. It’s a stark perspective of criminality and mental illness, and it also uses quite an interesting plot point about embryonic television, where you have a bar with a huge TV set in 1950 — and the bartender, of course, is William Conrad.”

1 p.m.: “Blood on the Moon,” directed by Robert Wise

“Robert Mitchum ditches his fedora and trench coat for a Stetson and chaps. This was Robert Wise’s first A-picture debut, adapted from a novel by a female screenwriter by the name of Lily Hayward who had really a interesting Hollywood career from the ‘30s onward, and lensed by the ace noir cinematographer Nicholas Musuroca. It really was the forerunner of a darker genre of Westerns.”

4 p.m.: “The Naked City,” directed by Jules Dassin

“A classic policier directed on location in New York by Jules Dasson, produced by Mark Hellinger. It’s really his cinematic valentine to his beloved New York. It established the prototype police procedural, written by Melvin Weld who haunted lineups, interrogations and autopsy rooms to create an ultra-realistic story of a NYPD murder investigation, led by a cast-against-type Barry Fitzgerald. The thing that’s also cool about this: this movie’s been shown a lot — I’ve never shown it — but this is a digital restoration that was done in Germany from Janus Films, and it’s never looked better or sounded better.”

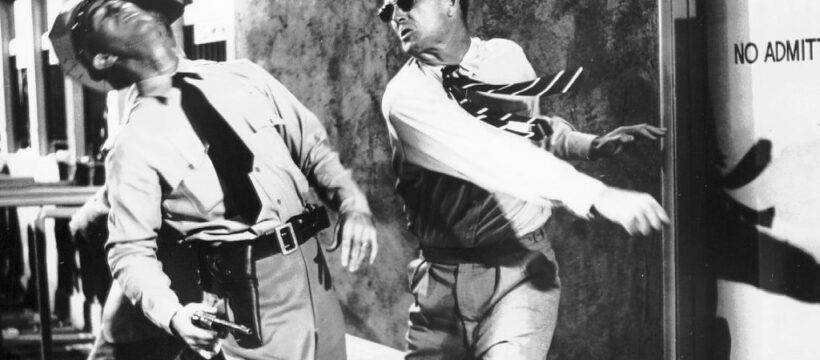

7:30 p.m.: “This Gun For Hire,” directed by Frank Tuttle

“Adapted by the Hollywood 10’s Albert Maltz and the great W.R. Burnett; an adaptation of Graham Greene’s novel. it was the initial screen pairing of Ladd and Veronica Lake. And this made Ladd a star instantly as a sympathetic killer for hire. In the early part of the movie, there’s a scene where he treats a cat with great gentleness. So I knew whether this guy was a hired killer or not, I was gonna love him, right?”

Saturday, May 13

8 a.m.: An early-bird screening of a recently restored 35mm print, presented by the Library of Congress and the Film Noir Foundation for passholders only

10 a.m.: “Decoy,” directed by Jack Bernhard

“You have a disturbed doctor, a murderer brought back to life after being executed in the San Quentin Gas Chamber, and a great femme fatale performance by a forgotten actress named Gene Gilley, who died young, who gives Ann Savage a run for her money. A greatly entertaining film.”

1 p.m.: “The Bigamist,” directed by Ida Lupino

“Shown in 35mm. I think this is the first instance of a female Hollywood star, in the case of Ida Lapino, directing and producing the film and directed herself. It’s really a groundbreaking study of a salesman played by noir everyman Edmund O’Brien, who’s married to a pair of women, Ida Lapino in L.A. and Joan Fontaine in San Francisco, and he’s keeping house with them in different cities. Lupino’s partner was her ex-husband, Collier Young; they got divorced in 1951 so Collier Young could marry Joan Fontaine, who was the co-star! I mean, you can’t make this stuff up.”

4 p.m.: “Appointment with Danger,” directed by Lewis Allen

“Another 35mm print. Alan Ladd is a no-nonsense postal inspector who will stop at nothing to solve the murder of a coworker by a robbery gang. And this has a great supporting task, including a duo of low-life crooks that are played by Jack Webb and Harry Morgan, prior to their assignment to the LAPD day watch on ‘Dragnet.’”

7:30 p.m.: “The Shanghai Gesture,” directed by Josef Von Sternberg

“This restored 35mm print was provided by the George Eastman House. It’s the only one. A Pressburger film directed by the great Joseph von Sternberg. The only way I can describe this film is a melodramatic fever dream, an adaptation of John Colton’s play that the censor’s office in Hollywood banned for 15 years until Arnold Pressberger and Von Sternberg managed to get their script approved. A rarity, with young Gene Tierney as a British thrush, Victor Mature wearing a fez as Dr. Omar and Walter Huston as a British expat attempting to buy a casino. They had to turn it into a casino rather than a bawdy house as in the original play.”

Sunday, May 14

10 a.m.: “The Lady Gambles,” directed by Michael Gordon

“Barbara Stanwyck’s marriage and life hit bottom after she becomes addicted to gambling. This was written by Roy Huggins, of ‘The Rockford Files’ and ‘Maverick’ fame on television. It’s really a time capsule of early Las Vegas, since it was made in ’49. Steven McNally, who kind of plays a Bugsy Siegel clone, reels in Stanwyck at his casino that was named the Pelican, which doubles for the Flamingo that had opened three years earlier. Rarely shown, and pretty good.”

1 p.m.: “Scandal Sheet,” directed by Phil Karlson

“Adapted from Sam Fuller’s novel, ‘The Dark Page.’ A real sharp-elbowed tale of a tabloid reporter played by John Derek, digging up a scoop on a murder that his editor, the perpetually bellicose Broderick Crawford, wants him to write about, but is trying to cover up at the same time, featuring a young Donna Reed and great cast.”

4 p.m.: “Double Indemnity,” directed by Billy Wilder

“We wrap up with a film I’ve never shown before that is probably the most emblematic film of film noir. It really established what would become recognized as the quintessential film noir style, with the voiceover narration and the flashback. One of Hollywood’s all time best screenplays as composed by Wilder and Raymond Chandler, adapted from James M. Cain’s novel. And Raymond Chandler actually has a brief cameo sitting in a chair in the insurance office. I’m sure many people have seen it, but if you haven’t seen it on the big screen, you haven’t seen it.”

Individual ticktets are $14.50, and a full festival pass for all 13 films plus opening night party is available for $149. Screenings will take place at the Palm Springs Cultural Center, located at 2300 E. Baristo Road.

Tickets can be pre-purchased here.

Read More About:

Source: Read Full Article