More On:

mennonites

Clinic opens drive-thru coronavirus testing for Amish, Mennonites

Mennonite murder mystery: Body identified as missing devotee

Mennonite investigator agrees to testify after beliefs land her in jail

Brother accused of abducting sister to prevent her wedding

In a case that made national headlines, Mennonite Robert L. Bear was excommunicated in 1972 for questioning church leaders and accusing them of hypocrisy — and treated sympathetically by the press for doing so.

A New York Times story from July 1973 called him “the model of raw‐boned American Gothic” and said he “seemed oddly cast as a heretic.”

But behind the scenes, Bear was far from an inspirational iconoclast. He was an alleged abuser who menaced his wife and six children for years, his daughter Patty Bear told The Post.

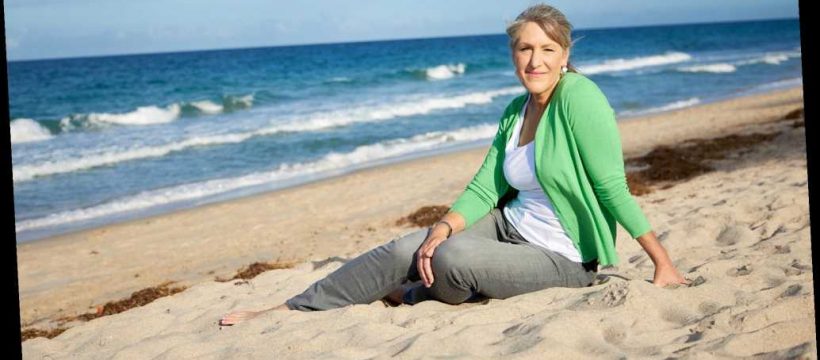

In her new memoir, “From Plain to Plane: My Mennonite Childhood, a National Scandal, and an Unconventional Soar to Freedom” (Barnstormers Press, out February 23), Bear shares how she broke away from the terrifying world her father created as well as the restrictive Mennonite community to become an accomplished Gulf War pilot, United Airlines captain and mother of two now-adult children.

“My father was a domestic terrorist,” 57-year-old Patty told The Post. “He took advantage because he knew we could not defend ourselves and would turn the other cheek.”

After Bear’s excommunication, in accordance with Mennonite doctrine, he was shunned by the 70 or so members of the church, including his wife, Gale.

Gale’s decision to take the “side” of the ministers infuriated Bear and rocked the couple’s marriage, Patty wrote in the book. She claims that Gale tried to observe the rules of the excommunication but was rendered helpless against his demands for conjugal rights.

The muscular six-footer became unstable and turned violent — often chasing Gale around the kitchen, tackling her to the floor and clawing at her breasts, Patty writes.

Despite moving out to a trailer on their 400-acre land, she said he would show up at the house unannounced and continue the “guerrilla warfare.”

“I once came back from working on the farm to find two of my younger sisters in shock,” said Patty. “He’d burst into the bathroom, screamed vulgarities at Mother as she bathed and made her curl into the fetal position for self-protection.

“She started singing a hymn to calm herself before suddenly flipping up, ducking under his arm and running naked out the door.”

Bear never beat his two sons and four daughters, but would give them mind-bending “loyalty tests” to prove their love for him, Patty wrote in the book. Other methods to punish the household allegedly ranged from withholding money to shutting off the heat and electricity in the depths of winter.

At the same time, much of his rage was directed toward the Mennonites, whose dogma, he claimed, had deprived him of his wife and children.

Of behavior described in her book, Patty told The Post: “He regarded us as his property and assumed he held a ‘claim’ on Mother similar to owning an animal. He would shout at the ministers: ‘Give me back my heifer!’”

The church allegedly provided little help. Eager to downplay the issue, Patty remembers that Mennonite leaders said Gale was “acting under her own free will” to shun her husband and failed to address the fact she would be excommunicated herself if she did not.

Reformed Mennonite Bishop Glenn Gross told The Post that the church had acted appropriately. He said: “It was Gale’s own convictions that told her to do this [the shun].”

Gale steadfastly refused to comment to the press, even as news stories increasingly shared only Bear’s side of the story: That he was miserable because he was unable to see his family.

Distraught by the increasingly warped narrative peddled by her father, Patty, then still only 9, begged Gale to set the record straight. “Jesus commands us to turn the other cheek,” came the reply.

The family fled the farm shortly thereafter and spent the next decade living in fear of Bear’s random offensives, Patty wrote. According to her, those allegedly included sledge-hammering his way into their new home, death threats and occasional kidnappings of his offspring.

“The police would arrive and charges rarely filed, though a judge once ordered him to undergo a three-day psychiatric evaluation,” Patty claimed. She said an “erroneous” 1977 report, detailed in the book, concluded her father was a “mild man who seems incapable of violent behavior.”

In 1979, Bear was arrested for snatching Gale from a local farmer’s market but was acquitted by the jury — even after Gale accused him of rape while testifying. The Washington Post subsequently gushed about Bear’s “uncanny resemblance to the late actor Gary Cooper in manner and voice.”

“Not that they do now, but this happened when people didn’t understand the dynamics of domestic violence,” said Patty, who left the Mennonite faith at 18 for a military career in direct opposition to its pacifist rules. “But I despaired the failure of anyone to see the truth.”

Patty decided not to join the Mennonite church herself — membership is reserved only for adults — because she became increasingly disturbed by its attitude towards women. “I had seen the way they were treated and their subservience,” she said. “I knew I didn’t want that for my future.”

She decided in 1981 that she would turn her back on the sect and joined the Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs, Colorado, the following year.

Meanwhile, her father published a book, “Delivered Unto Satan,” as part of his five-decadeslong crusade against the Reformed Mennonite Church. Now 92, Bear continues his protests and was jailed in 2017 for vandalizing a place of worship. In December 2020, he was arrested again for defacing the church, papering it with manifestos about his ex-communication plight.

When reached by phone, Bear denied the domestic-abuse allegations and also claimed that intercourse with his wife was consensual.

Gale, 82, died earlier this month at her home in Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania. Although she “never wanted publicity,” she gave her blessing for Patty’s book last year. Patty was laid off from United Airlines in the fall of 2020 and is no longer flying.

As for her father, the author wrote that she feels no need to forgive him. “He hasn’t asked for it and he doesn’t seem to feel he needs it,” she wrote in the memoir. “Allowing myself to be angry is one of the more healing things I have experienced.”

The purpose of the book, as she told The Post, was to “share with people the standard operating procedure of abusers.”

Then, citing the last five words of its powerful subtitle: “an unconventional soar to freedom,” Patty concluded: “Sometimes trauma can be a path to liberation.”

Share this article:

Source: Read Full Article