British-born woman from Nigerian family who was fostered by a white English woman until she was 6 reveals she had to adapt to a life of ‘threat, censure and labour’ when they moved back to Africa in moving new memoir

- Florence Olajide was just six-years-old when she was torn from her London home

- She’d spent first years of her life being mostly looked after by an English woman

- But soon her African parents decided to move back home with their children

- Florence was left traumatised by the culture shock she went through and has now written a touching memoir about her experience struggling to fit in

A British-born woman has revealed the trauma she suffered after moving to Africa aged six with her Nigerian parents and finding ‘every day a struggle as she hit a cultural expectation she wasn’t aware of’ in a moving memoir.

Florence Olajide, now 58, was one of a generation of Nigerian children born in Britain in the fifties and sixties privately fostered by white families, then taken to Nigeria by their parents. Her newly released book Coconut is the moving story of how this impacted her life.

The educator spent the first years of her life being looked after by an English woman called ‘Nan’ in London, while her parents worked and lived in another part of the city.

At the tender of age of six, Florence suffered her first experience of racism following a dispute with a classmate who called her a ‘monkey’ – but nonetheless she was happy.

Until one day, her parents told her their family would be returning to Nigeria, a then war-torn country, and leaving her much-loved Nan and her friendly household behind in England.

As soon as she stepped off the plane in Africa, Florence noticed the differences – from the suffocating heat to being labelled the term ‘white’ by intrigued relatives because she came from abroad.

But later, the stark contrasts between Florence and her immediate family were still showing, as she notes in her book of one particular experience where she struggled to carry water to a relative’s home unlike her adept cousins.

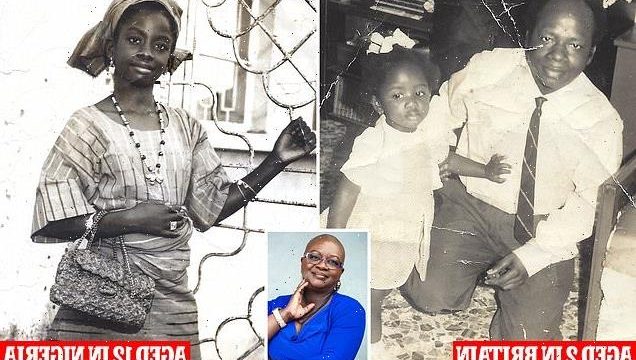

Florence Olajide (pictured aged two, with her father), now 58, was one of a generation of Nigerian children born in Britain in the fifties and sixties privately fostered by white families, then taken to Nigeria by their parents. Her newly released book Coconut is the moving story of how this impacted her life

The educator (pictured) spent the first years of her life being looked after by an English woman called ‘Nan’ in London, while her parents worked and lived in another part of the city

‘Once more, that evening, my water escapade provided all the dinner-time entertainment the family needed,’ she recalled.

‘As I lay on a mat that night, listening to my snoring relatives, I once again pondered my existence. Here I was, in a country full of people who looked just like me. I should be one of them, but I wasn’t.

‘I felt different; they knew I was different, and if I didn’t fit in here, where exactly did I fit in? I went to bed thinking of Nan, Dee, Tom and Pop [her foster family].

‘I wondered what Dee was up to these days and imagined his expression had I been able to tell him some of my experiences.’

Florence admitted she was a ‘rebellious and deviant’ child, and as such she often crossed paths with her grandmother, Mama, who believed in severe corporal punishment, which some of the author’s teachers were also fond of.

The West African children privately fostered by families in Britain in the 1950s to the 1970s

From the 1950s to the 1970s, it was not uncommon for West African children to be privately fostered by white families in Britain.

Many of these youngsters were born to Nigerian and Ghanaian students who would often hold down jobs alongside their studies and not have time to look after their children.

As such, they’d make arrangements for private foster care which was perfectly legal at the time, reported ITV.

Thousands of families were paid by African parents to care for their children, with the Times in 1968 recording up to 5,000 youngsters having been privately fostered.

Most children would return to their families, but their start in life undoubtedly had a huge influence on the rest of their lives.

Speaking to FEMAIL, Florence explained: ‘Every day was a struggle as I hit a culture expectation that I wasn’t aware of, that was the challenge, that I wasn’t prepared for it.

‘I suspect that if I’d lived in England with my parents it wouldn’t have been as hard because some of the social norms and expectations would’ve been passed down.

‘There are certain things I would’ve learnt already before we moved that I didn’t get to learn because I was living with my foster mum, so therefore the opportunity to offend was higher.’

Even after two years of living in Nigeria, Florence’s different start in life compared to her peers found her struggling to fit in.

‘By now, I hated most things about my life. My days were long, filled with labour, censure and threat, but my nights were even longer, filled with longing for my previous existence,’ she admitted in her memoir.

‘I dreamt of the day I would return to England and often pictured myself running into Nan’s arms, the terror of Mama and [teacher] Mr Adesanwo a long-forgotten nightmare.’

Before moving back to Britain permanently with her children and husband to work as a primary headteacher in the 1980s, much of Florence’s memoir is filled with a need to return to England.

‘It was the challenges I had with my grandmother and my extended family, because I didn’t fit… and couldn’t find my place there, so that was a driving force in terms of me wanting to go back,’ explained Florence.

‘And as a child you remember the happy places and for most part of my life then I wasn’t happy, so there is a tendency to want to hanker for what you had.

‘I realise now as a grown up that I had painted it with rose tinted glasses as well but when you’re six, the world is alright in your eyes, so there was that need to get back because I wasn’t happy in my own context and because England represented happy memories for me.’

At the age of 18, Florence’s father finally agreed to let her return to England to visit Nan, who she had sporadically kept in contact with over the years through letters.

At the tender of age of six, Florence (pictured, aged 12) suffered her first experience of racism following a dispute with a classmate who called her a ‘monkey’ – but nonetheless she was happy

But when in her hometown, Florence’s ‘rose tinted glasses started becoming a bit more real’, noticing the grey weather, the gum-plastered pavements and the overall uncleanliness.

Florence added: ‘I was still very contented to be back, but I kept weighing things up so all the way through the six weeks I kept weighing up what I’d left with, where I was, what I had, what I was leaving behind, “Did I want to stay? Yes”, but “Could I leave? No”.

‘I kind of pushed it to the back of my mind for a while but as the last week of that trip got closer that’s when that feeling of being torn about what you want, and the reality of your context, made me sort of think this is going to have to wait for another day.’

Eventually, after starting their family in Nigeria, Florence and her husband Bade returned to the UK with their children to begin a new life together.

‘When I returned here, I felt I’d come home,’ said Florence. ‘And home is still here for me. I know that extended family members struggle when I say that.

‘I still remember once my mum mentioning about how one of my great uncles started weeping when he heard that my siblings and I had all left, because he kind of felt like he’d never see us again and he didn’t.

‘In England, we say home is where the heart is, over there we say home is where your ancestors are,’ explained Florence, who added that she struggled with ‘almost everything’ about the culture.

Until one day, her parents told her their family would be returning to Nigeria, a then war-torn country, and leaving her much-loved Nan and her friendly household behind in England. Pictured, Florence

She added: ‘For me, you don’t miss something that gives you a lot of anxiety but that’s more about me and who I am because I’ve got friends that love going back, and go on holidays there.

‘But for me, it immediately brings up anxiety levels that I’m going to offend somebody at some point. It’s the trauma of my experience there, they leave scars. I have been back, and they haven’t been bad experiences, it’s just my anxiety levels go up.’

Yet even when returning home to Britain, Florence had to face questions over her accent and style, with people questioning ‘where she was from?’, and even one passport officer shockingly asking ‘when are you leaving?’ upon her arrival at Heathrow Airport.

‘It was [upsetting], in my head I understand why they were asking, because I had a different accent and they were curious,’ recalled Florence. ‘But it didn’t change how I would feel. [I would think] “they can still tell I’m not from around here so I need to do something about that.”‘

But towards the end of her book, Florence, who now works as an independent education consultant, admitted that she had embraced more of the African culture than she realised and will continue to teach her family about the aspects she values – such as the sense of community and looking after the elderly.

As soon as she stepped off the plane in Africa, Florence (pictured) noticed the differences – from the suffocating heat to being labelled the term ‘white’ by intrigued relatives because she came from abroad

‘There’s values from the culture that are important to me and I still use and raise my children and my grandchildren by so there are aspects of the culture that I do value,’ she insisted.

However, despite saying she now understands why her grandmother would use physical punishment, having been taught that way, she said ‘it was not healthy for any child,’ and was ‘harmful for me’.

‘I can look back now and kind of process why she did what she did and understand the culture and how the culture works, but it doesn’t change the harm – physical or mental – that would result for a child,’ she said.

But Florence isn’t one to think about ‘what ifs’ – refusing to linger on how different her life would’ve been if she’d have spent her first years with her parents, or never left Britain.

Instead, she said she finally understands the importance of realising you don’t have to be one culture or the other.

‘I think the initial issue was about being “either this or that”, but once I got to that point where I was more than one or two things, I was multifaceted with lots of different parts to me, that helped.

‘You can create your own identity. It’s that realisation that you don’t have to be one or the other you can create a third path and be yourself and once you find the strength to do that you’re in a better place.

‘I’m not a “what if” person… everything that happened before has lead to where I am now, it’s all part of the same story. So I can’t be happy with who I am now and then want to reject something that’s happened in the past.’

Coconut – A black girl fostered by a white family in the 1960s and her search for identity and belonging by Florence Olajide is published by Thread, 13 July.

Florence will be speaking at this year’s Primadonna Festival (30 July – 1 Aug) at the Museum of East Anglian Life in Suffolk.

The festival have just launched their Pay What You Can ticket scheme to make it accessible for all. Day or weekend tickets available – www.primadonnafestival.com

Source: Read Full Article