Observers of the art market have referred to the rising demand for work by contemporary African-American artists in recent years as, among other things, a “furor” or “surging,” and the work itself as “a hot commodity.” Ten years ago, it was relatively rare to see a Black artist’s work set a record at auction. Now, such sales are routine, boosted by numerous high-profile lots, perhaps most famously Kerry James Marshall’s 1997 painting “Past Times” (purchased by the rapper and music producer Sean Combs for $21.1 million at a Sotheby’s sale in 2018) and, more recently, Jean Michel-Basquiat’s “In This Case” (1983), which sold at Christie’s in May for $93.1 million — an astronomical price, but still only the second-highest ever paid for a Basquiat.

T’s 2021 Art Issue

A look at the soul of the art world, and where it’s headed.

– Experts weigh in on just how to go about buying a work of art.

– What does “normal” mean to the art world now?

– The down-to-earth guy with one of the most exciting collections around.

– Artists on artists to know, and maybe even collect.

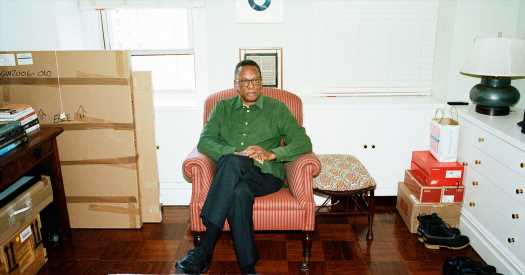

Given the hype surrounding such figures, it’s surprising that one of the more interesting collections of contemporary African-American art is housed inside a fairly humble Manhattan two-bedroom apartment on Madison Avenue. It belongs to Alvin Hall, 68, a broadcaster, financial educator and author, who, through good timing, taste and a bit of luck, began collecting in the 1980s and has been able to buy masterpieces by artists whose work is now worth much more. At a time when art — and Black art in particular — has been inflated and commodified to the point of a quasi-bank transaction, Hall is a model of best practices for nonbillionaires hoping to amass a world-class collection. His apartment also illustrates some of the realities of how to live with art when you only have a minimal amount of space: He owns 377 works, 342 of which are in storage.

The first work that greets you is on a wall that abuts the apartment’s front door, by the New York-born, California-based artist Gary Simmons. The words “again and again …” (the 2001 piece’s title) are stenciled at eye level in smeared blue paint. The work more or less points to the living room, a few short steps away, where the eyes bounce around from piece to piece. Toward a window that grants a peek at the East River — and almost directly beneath a portion of the wall that was recently water damaged by some upstairs neighbors failing to clean their outdoor terrace — is Lorna Simpson’s “7 Mouths” (1993), which contains seven panels, each displaying a black-and-white image of a closed mouth, grips the attention and renders the East River powerless. In the bedroom, past an installation atop a sideboard in the entryway by the Ghanaian sculptor El Anatsui, a Lee Friedlander photograph of a New Orleans street scene hangs next to a window air-conditioning unit. In the office, two cleavers are stuck forebodingly into the wall, an installation by Barry Le Va, the influential sculptor who died this year. But the star of the apartment is Carrie Mae Weems; pieces from her series “From Here I Saw What Happened, and I Cried” (1995) are framed dramatically in the living room above a dining table. (The work totals 65 pieces, and Hall owns four of them; he recently moved them from the bedroom.) A series of appropriated 19th- and 20th-century daguerreotypes of slaves that spell out the array of atrocities Black people encountered after arriving in this country against their will, Weems rephotographed the images and printed them through colored filters, giving them a haunting beauty and, as she once said in an interview with the Museum of Modern Art, providing “a voice to a subject that historically has had no voice.”

“I’ve always had something that I collected,” Hall said during a recent visit to the apartment. “When I didn’t have any money, I would go through yard sales and go through boxes of photographs. There has always been a little bit of something I’ve collected just for the fun of it.”

Just for the fun of it is hardly the philosophy that guides most contemporary collectors, but Hall came to collecting through unlikely circumstances. He was raised on a subsistence farm in Wakulla County in the Florida panhandle, corralling hens and harvesting pole beans, black-eyed peas, okra and corn. “I never knew you could buy eggs from a store until I was about 11,” he said. The walls of the farm — which has been with Hall’s ancestors since 1868 — were unadorned during Hall’s childhood, save for a few key objects: photos of President John F. Kennedy and the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and a velvet rendition of the Last Supper. There were not even family photos, let alone contemporary art.

But Hall took a cue from his grandmother, Rosalie, who lived through the Great Depression. According to Hall, Rosalie had a reputation for frugality, always heading to the bank to put something away. She perpetually demonstrated the importance of saving money for a rainy day, and Hall absorbed her thriftiness from a young age. Today, he lives across the street from the Morgan Library & Museum, but until the age of 16, Hall wasn’t aware that museums even existed. “There were no museums in Wakulla County,” he said. The family could only visit the museum in nearby Tallahassee on the anointed “Negro Day,” “which we never did since we didn’t have a car,” Hall continued.

A dedicated student, Hall gained entry to the Yale High School Summer Program in 1969, where he experienced just how far New Haven, Conn., was from rural Florida. The Black Panthers had a headquarters in New Haven, and the town’s mayor, Richard C. Lee, famously spoke out against the Vietnam War and urged President Richard Nixon to bring troops home. This hotbed of political activity gave Hall his introduction to contemporary art. The Swedish-born American artist Claes Oldenburg, as a show of support for student protesters opposed to Vietnam, installed a 24-foot-tall sculpture of a tube of lipstick, unraveling from inside a military caterpillar tank, at Yale’s Beinecke Library Plaza. Hall would spend hours staring at Oldenburg’s work. It hounded his mind. Everything happening at Yale was just in the background. “It was that good,” he said, “and I didn’t even know that there was such a thing like that. I thought art was just classical paintings in books.”

Graduating from Bowdoin College in Maine in 1974 with a degree in English Literature, Hall was in debt, but he spent his time looking and pondering, “building a well of visual images that have since influenced what I collect,” as he put it. In 1982, he moved to New York and started working in finance, which gave him money for the first time in his life. He became friends with Marvin Heiferman, who worked in the print department at Leo Castelli, the dealer of artists like Warhol and Rauschenberg. In another sign of Hall’s foresight, he bought two photographs by Nan Goldin from her 1985 series “The Ballad of Sexual Dependency,” which documented the nocturnal and narcotic lifestyles of Goldin’s friends. He bought “Skinhead Having Sex, London, 1978” and “C.Z. and Max on the Beach, Truro, Massachusetts, 1976” (the titles are self-explanatory) for $350 each. Individual works from the same series have since sold for over $65,000.

Gradually, Hall started to collect work by Black artists of his generation, who were at the time largely absent from the walls of galleries and museums — meaning there weren’t many collectors interested in the ’80s and ’90s, either. At the time, there simply weren’t a lot of options for a Black collector interested in contemporary Black artists. “The African-American art wasn’t what it is today,” Hall said. “You didn’t have that many actual players.”

But he made it his mission to find and collect the work. At a New York gallery in 1991, Hall saw Lorna Simpson’s “Back (Eyes in the Back of Your Head)” (1991), an austere photographic study of the back of the artist’s head, and he felt he had to own it. Simpson represented, in the words of the critic Elvan Zabunyan, “the first time in the history of American art” that “a woman artist was engaged in a conceptual practice that addressed both African-American cultural history and the memory of slavery, … as well as political consciousness and critical thought.” This made her very much an exception in the art world. (A somewhat infamous 1990 article in New York Newsday about Simpson pointed to her solitary position as a Black woman making work about Black women with the headline “The Outsider Is In.”) For Hall, Simpson’s work has always stayed with him. He describes it as open-ended, emotional and powerful but, most important, Black. Two years after first encountering her work, he bought Simpson’s “7 Mouths,” which he still owns, and it’s now the work that’s most frequently borrowed for exhibitions.

The idea that Black art has been undervalued is a fairly new phenomenon. It is due, in part, to a broader curatorial reassessment intended to elevate the artists of color whom art history has, until recently, tended to automatically marginalize. This has led to artists in Hall’s collection becoming highly coveted on the secondary market. (Weems’s and Simpson’s works, for instance, are trending toward the mid-six figures, having fetched $237,500 and $375,000, respectively.) As the landscape has grown and become more inclusive, all those auction records for Black artists also distract from certain systemic failings in the art world that have not changed: Gallery owners in Chelsea, New York’s main arts district, are still overwhelmingly white, as is the Art Dealers Association of America, a nonprofit organization comprising some of the world’s most powerful galleries, as well as the exhibitors at most major art fairs like Art Basel.

In the late ’90s and early aughts, as the market for contemporary art became more competitive, Hall recalls that art collecting began to shift from an emotional response to one about profits. Art became an asset class, and those who did buy wanted to get a return on their investment. Gradually, collectors began trying to identify the next hot trend, an artist someone could pay $20,000 for today and sell for $250,000 in four years. “That’s when everything started to change,” Hall said.

Hall has never been interested in holding on to art to resell later. It was Simpson’s potential and power that drew Hall to her work, which remains a guiding force in his taste to this day. He struggles with the idea of being priced out of art collecting, but quickly remembers why he does so to begin with. “I want to see what happens with some of these artists,” Hall said. “Some of them have the potential to be big breakout stars.”

The rise in value from when Hall began collecting to now creates other logistical issues. At one point, his art insurance bill was as much as his mortgage, so he has had to sell several pieces to bring the overall value of his collection down. But when he does sell his work, he puts some money into retirement, some into savings and then he takes a certain percentage to support a contemporary artist. For Hall, the art world has always been about giving more than you get.

Source: Read Full Article