The world is broken. Humans shuffle in place, burdened and anxious, glued to tiny screens, living fossils in an archaeology of traumas — racial, economic, ecological — that all seem activated at once. Faced with a pandemic, political and economic leaders have proven unequal to the challenge of steering their people, and the planet, to safety. The playbook is empty. They have defaulted to mediocrity, surveillance, the algorithm.

This compound failure is a failure of imagination. But if the powerful have run out of ideas beyond clinging to wealth and control in the face of catastrophe, art reminds us that there are other options. And so this season more than ever, I am looking to art that refuses to abdicate: exhibitions and projects that offer global range and historical insight, that tap into ancestral and community knowledge, that beckon us toward constellational thinking.

The New Museum Triennial (Oct. 28-Jan. 23) should be a good start. The triennial’s established mission — to present emerging artists from all over the world — is crucial in this period of national isolation; and this edition’s theme, to do with overlooked materials, decay and renewal, seems apt. I’m excited that it includes the prodigious young South African artist Bronwyn Katz, whose sculptures of copper, iron ore and found objects are aesthetically concise — not to say Minimal — yet uncannily charged with spirit force from that country’s geologic and social terrain.

Also on my triennial radar: the quasi-shamanic sculptures of Evgeny Antufiev; the Indigenous performance-based artist Tanya Lukin Linklater, who is from Alaska and lives in rural Ontario; and the multimedia artist Thao Nguyen Phan, co-founder of an artists’ collective in Ho Chi Minh City that embeds in local communities.

I often think of the 1970s, when competition between nations (and dissidence within them) opposed real social projects — European social-democracy, Third Worldism, the various strains of Communism — before the Reagan-Thatcher “revolution” ushered in the hegemonic cult of finance. It was a turbulent time with plenty of failed experiments, but it produced thinking with purpose, offering glimpses of a better world.

What if global resource transfers had happened, as recommended in 1980 in North-South: A Program for Survival, the report of a commission chaired by Willy Brandt, the former German chancellor who knelt in contrition for the Holocaust and made peace with the East? On the art front, back then, much European opinion and even establishment figures supported the restitution of works looted in colonial wars, an idea only now making some laborious headway. What if that humanistic logic had prevailed all along, instead of crude market power and zero-sum thinking?

We’ll never know, but in the work of contemporary artists informed by the aspirations and illusions of that period, we can perhaps find insight for the present. What could a global consciousness be today?

At Amant, in Brooklyn, a show by Grada Kilomba (through Oct. 31) uses installation and performance video to examine postcolonial trauma using Greek myth and psychoanalysis. At the same venue, Manthia Diawara (Nov. 11-March 27) will premiere a multichannel work drawing on the work of Édouard Glissant, the Martinican philosopher who claimed for the oppressed the “right to opacity” — to not explain. Diawara was a friend of Glissant, who died in 2011; his film features, among others, David Hammons, Danny Glover, Wole Soyinka and Maryse Condé.

In her four-part “Who Is Afraid of Ideology,” the filmmaker Marwa Arsanios examines new liberation movements — ecological and feminist — in Kurdistan, Lebanon, Colombia; the full project shows this season at the Contemporary Art Center in Cincinnati (Sept. 17-Feb. 27). Here in New York City I’ll be seeking out international work — for instance by the Indian photographer Gauri Gill, at James Cohan (Oct. 7-Nov. 13), and the exiled Myanmar painter Sawangwongse Yawnghwe, at Jane Lombard (Sept. 10-Oct. 23) — for its subject and style, but also for connection across the chasm of travel bans and vaccine inequality. (Here’s to the artists, art handlers and gallery staff producing shows under these conditions.)

I hope the Prospect 5 triennial in New Orleans, already postponed from last year by the pandemic, is able to take place as planned (Oct. 23-Jan 23). The program is rich, with a strong share of local artists as well as interventions from nonlocals (Kevin Beasley, Simone Leigh, the London duo Cooking Sections and more) that should illuminate how a major art gathering can be productively woven into its host community. This is always an issue for biennials, but Prospect — which originated in the wake of Hurricane Katrina — can, I hope, set an example, following this fresh trauma, for other cities to emulate.

Louisiana-made projects are coming to New York as well, with Dread Scott’s photography and banners from his 2019 community re-enactment of a slave rebellion, at Cristin Tierney (Sept. 17-Dec. 18); and Dawoud Bey’s photography and video of plantation sites, at Sean Kelly (Sept. 10-Oct. 23).

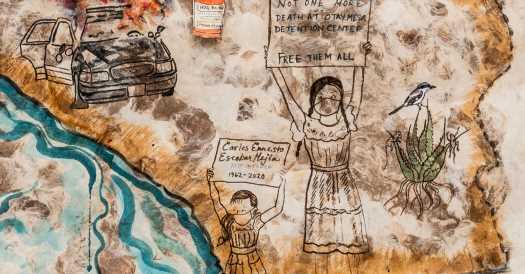

If you can hit the road, however, you might journey onward to the Texas Biennial, which presents 51 artists across five museums in Houston and San Antonio (through Jan. 31). The Dallas Museum of Art has the first museum solo of the spiritually minded painter Naudline Pierre (Sept. 26-May 15); the Amon Carter Museum of American Art in Fort Worth presents works on paper by Sandy Rodriguez (Dec. 18-April 17), combining inspiration from California desert flora with last year’s social upheaval and lockdown isolation.

I’m not looking for “pandemic art” per se — we’re still deep in it. But the world-historical shock we’ve gone through since March 2020 is slowly but surely becoming channeled in major artistic creations.

“Five Murmurations,” the new video installation by John Akomfrah at Lisson Gallery (through Oct. 16), is a “filmic archive of today” from the British director whose career, from works on race and class in the 1980s to recent projects on the oceans and climate change, tracks how we got to this point.

And at the hyperlocal level, I look forward to the first public programs in the Queens Museum’s “Year of Uncertainty.” The museum — with an already strong record of creative engagement with its borough — is working with artists in residence and community groups to interpret, and reflect in the museum’s own culture and projects, the existential challenge of our time.

It is not from the halls of power, but rather from places like Queens — hard-hit by the pandemic’s first wave, but also dynamic and diverse, connected through its immigrant population to most of the world — that we stand to gain robust insight, even hope, as we work our way out of the ruin.

Source: Read Full Article