This article appeared as the cover story for Hypebeast Magazine Issue 32: The Fever Issue. Please visit HBX to grab your copy.

In an airy studio off London’s Brick Lane, Mowalowa Ogunlesi— founder of her eponymous brand Mowalowa—is working on “Crash,” her upcoming SS24 collection. “The name comes from David Cronenberg,” the designer says. “But I don’t want to share too much. There’s nothing worse than a spoiler to a good movie.” Ogunlesi splits her office with a team of 11, who’ve been playing Nigerian rapper Deto Black and producer Kingdom on repeat as they progress on the brand’s sixth collection. She rearranges the furniture and studio layout every few months to keep things feeling fresh, much like the brand’s fast-evolving output.

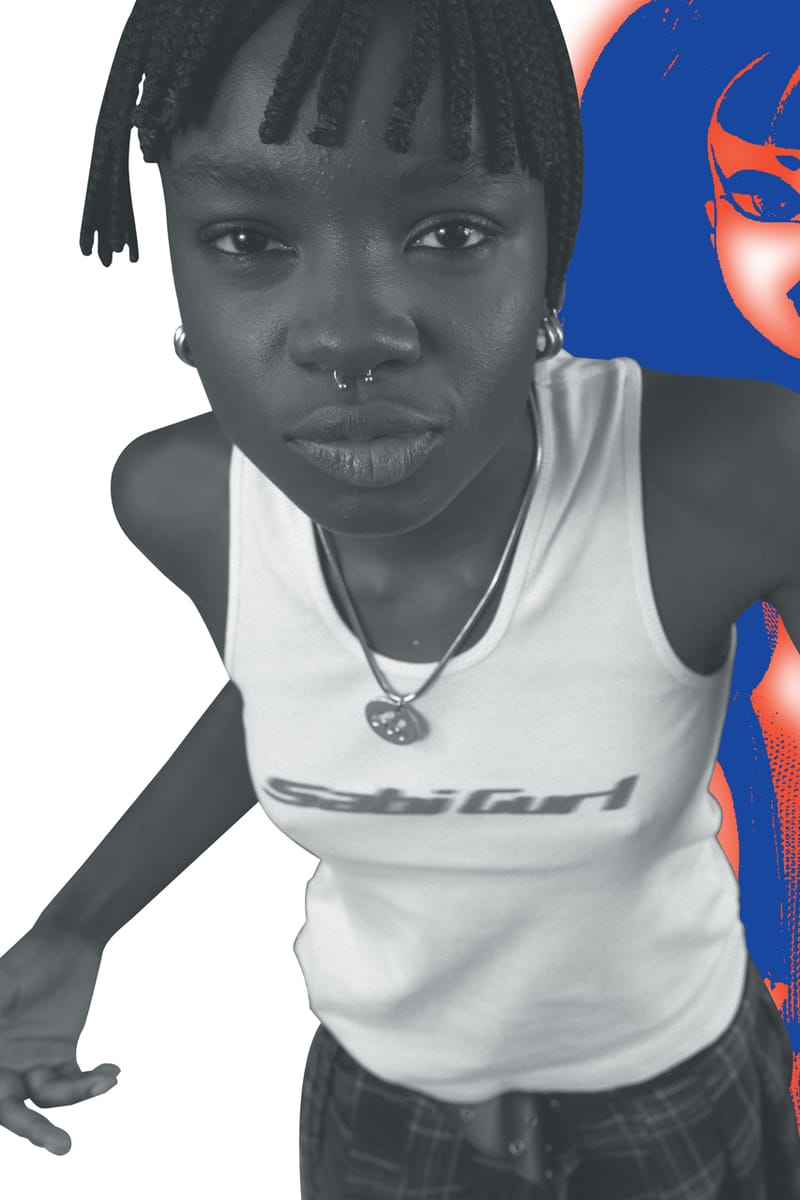

At age 28, the Lagos-born, London-based designer helms one of the world’s most promising young labels. Mowalowa, officially founded in 2017, is known for PVC and leather designs, bold cut-outs, colors that pop, diasporic cultural references, and wide-ranging themed collections. More recently, you might have clocked the brand’s t-shirts and trucker caps with bootleg and Y2K-inspired logos and motifs. Ogunlesi’s designs have been worn by Solange, Kelela, Kim Kardashian, and Skepta, as well as Naomi Campell—who wore a Mowalowa white halter- neck dress featuring a bullet hole that dripped scarlet during London Fashion Week in 2019. The outfit was interpreted as a direct comment on gun violence, but Mowalowa clarified it was from the collection “Coming for Blood,” inspired by the “horrific experience of falling in love,” as well as (more broadly) feeling like a constant target. “I make clothes to challenge people’s minds,” Ogunlesi wrote in an Instagram caption. “This dress is extremely emotional to me—it screams my lived experience as a Black person.”

Courtesy Of Mowalola

Elsewhere, Ogunlesi has designed uniforms for Nigeria’s World Cup team on behalf of Nike, and dressed Barbie on her 60th anniversary (prior to the Greta Gerwig film). More recently, Ogunlesi’s off-schedule show during Paris Fashion Week SS23, styled by fashion visionary Ib Kamara, took unexpected inspira- tion from those who steal, with looks referencing a vast array of criminals from white-collar bankers to “Yahoo Boys”—Lagos internet scammers. “Mowa’s vision is beyond beautiful,” Kamara tells us. “She has a way to connect with people through her storytelling, which is so rich and vibrant—in your face, but well thought through.” For AW23, the theme was “Dark Web,” a col- lection conjuring dystopian techno-capitalism with hacker references, makeup that subtly blended man and machine, and signature Mowalowa-style takes on logos ranging from the New York Yankees to MoMA.

Before she achieved global renown, Ogunlesi first caught the UK fashion industry’s attention during her 2017 graduation show at Central Saint Martins, themed “Psychedelic”—an homage to Lagos petrolheads and 1970s Nigerian psychedelic rock. Ogunlesi was picked up by Fashion East, the UK fashion incubator that helped launch the career of Dior’s Kim Jones, and, more recently, Ogunlesi’s friend and contemporary, Maxamillian Davies. While starting to show with Fashion East, Ogunlesi cut her teeth at brands like Yang Li, Wales Bonner, and Celine, and was hired by YEEZY in 2020 to work on the YEEZY Gap collection, although she exited soon after. By the time the pandemic hit, she had two acclaimed Fashion East shows under her belt, as well as an exhibition, Silent Madness at NOW Gallery, that zoomed in on her work and the inspirations behind it. The exhibition featured a fashion film Ogunlesi made in collaboration with director Jordan Hemmingway, alongside specially-commissioned sounds from Yves Tumor, Shygirl, and others.

“I realized you can figure out your own path, rather than just doing what everyone else does.”

While Ogunlesi was already operating in non-traditional fashion contexts, the pandemic shook things up further, forcing her to rely less on wholesale accounts and pivot the brand to direct- to-consumer sales. The designer kept herself busy by recording and releasing music informed by cyber-core and trap, also under the name Mowalowa. The two years Ogunlesi paused from working at a breakneck speed led to a moment of recali- bration. “Now I’m operating with what feels good for me,” she says. “I realized you can figure out your own path, rather than just doing what everyone else does.” People like Telfar Clemens have shown that, she adds, referencing the US designer’s approach that bridges art, music, and fashion, all while achieving commercial success.

“The way I started my brand was not done in the stereotypical way of starting something. It just kind of birthed itself,” Ogunlesi explains. “The fashion calendar is important for any brand that’s managed to stay independent, but I think a lot of brands [that don’t follow it] have succeeded as well.” Instead, operating at her own pace now informs the way she collaborates with her team, something she learned from her time at YEEZY. “It was an ongoing development situation there,” she says. “Back then I was doing a lot of stuff by email. I realized I could work a lot faster by text, just cutting information barriers, and making things more fluid.”

Courtesy Of Mowalola

In Nigeria, Ogunlesi was raised by two fashion designer parents, while her grandmother ran a brand in the 1980s, as well. She credits her family for her creativity but not her career: “It didn’t really matter what my parents did; I feel like I would still do what I’m doing now,” the designer explains, adding that since her mother owns children’s clothing stores, their respective busi- nesses feel worlds apart.

Ogunlesi was inspired by her mother’s ethos, though: “When she advertised in Nigeria, she made sure people knew this brand was by Nigerians. I think that sparked a change in the apparel industry in Lagos. After colonialism, there wasn’t much national spirit and a lot of things were internationally bought and sold,” she says, noting that as a child she’d beg her dad to buy her Timberland boots and Reebok G-Unit sneakers. Today, that effect of Nigerian pride is displayed by homegrown brands that ripple beyond the continent. Ogunlesi mentions skate line Motherlan—who recently collaborated with Stüssy—or the streetwear brands WAFFLESNCREAM and Meji Meji.

Despite the outlook her mother instilled, before moving to London for fashion school, Ogunlesi says she “thought of fashion as like a very white concept—even when I would draw stuff, it’d be with white people.” It was seeing Wales Bonner’s final Central Saint Martins collection, entitled “Afrique,” with an exclusively Black cast, that led to a recognition that she could also do things differently. “I’d never seen that before beyond Nigeria. Seeing that outside of my home was really special, and changed the way I saw fashion. It became more personal to me. It also built a sense of trusting what feels good.”

“If you want to enter my world, there’s no bouncer checking IDs and saying, ‘No, you can’t get in.’”

Ogunlesi visits Nigeria a few times a year, giving her the freedom and energy to think. “I don’t feel boxed in or forced into a way of thinking that isn’t me while I’m there,” she notes. “There are references to Nigeria in the work. You might not get them if you’re not Nigerian.” That’s OK, says the designer, because the scope is broader—her designs also intend to harness the power of modern-day globalized youth culture. “I’m thinking about me, I’m thinking about other Nigerians, but also the people in my studio and our collaborators from all over the world who recognize what we’re trying to do creatively, people on the same wavelength. If you want to enter my world, there’s no bouncer checking IDs and saying, ‘No, you can’t get in.’”

Collaborators can come from anywhere, like Chinese visual artist Woozie, who Ogunlesi connected with online to work on the brand’s visuals. “These global collaborations feel like home because I grew up with a very international window of information. We’re all from different places, but we all know the same shit from the arts—music, film, popular culture, Nicki Minaj verses.”

Courtesy Of Mowalola

The designs produced with this spirit in mind feel high-energy, eclectic, and capture a sense of movement: jumping from place to place, showing up, and turning out. It’s clear that club culture was an early reference, with Mowalowa part of an East London community that congregated around the club night PDA, run by DJ and fashion multi-hyphenate Mischa Notcutt, musician MsCarrie Stacks, and filmmaker Akinola Davies. The party, which ran in the mid-to-late-2010s, usually in a Dalston base- ment, catered primarily for queer and gender nonconforming people of color. The lasting impact it had on Ogunlesi can be felt through Mowalola’s effectively genderless garments; Ogunlesi sees her designs as versatile and fluid. Studying print and working on prints that eluded gendered categories also informed this approach. “Right from the jump, my menswear and womenswear were one, I’m not about a conversation like, ‘Womenswear is this, menswear is this.’ I feel like gender is a spiritual thing.”

Although Ogunlesi won’t say too much about what’s up next, she shares that the Mowalowa palette is shifting. “I’m trying to challenge myself to use more muted tones and less bright primary colors, in terms of my growth and where I’m at now. Colors have reflected how I felt in a moment, and that’s what I’m feeling I want to wear.” Beyond design, her personal focus is continuing to manage the “always on” nature of the business.

“Life is chaos, so I just lean in.”

“I feel like I’ve just had to climb a crazy mountain. And now I’m about to take off from the top of it,” she says. “Every day feels exciting. But then I also just have to have extreme ease with everything—the industry, deadlines, whatever. Life is chaos, so I just lean in. I go with it. Because when I’ve been stressed, I miss things and I’m not present. For now, I just want to enjoy the moment.”

Source: Read Full Article