“By candlelight, my hand will write these rhymes ’til I’m burnt out,” MF Doom raps at the beginning of “?,” the final song before the epilogue on his 1999 debut album, “Operation: Doomsday.”

In its video, Doom is indeed at the end of his wick. He staggers through a park, clutching a machete in one hand and a bottle of Jack Daniels in the other. He’s roaming, unsteady. You feel for him.

The song concludes with an affectionate remembrance for his brother, Subroc, who was killed in a car accident in 1993. “My twin brother, we did everything together/From hundred rakat salahs to copping butter leathers,” Doom raps, then concludes the verse with a portrait of grief and resilience: “Truly the illest dynamic duo on the whole block/I keep a flick of you with the machete sword in your hand/Everything is going according to plan, man.”

Toward the end of the video, Doom is slumped on a park bench while he’s rapping this part, and that photo flickers on the screen; Doom had insisted it be included in the final clip. His boots are off, resting by the sides of his feet, and his signature mask is laying on the ground. His hand is spread across his face, both cloak and shield. The sadness in his eyes is practically wet.

Sometimes on “Operation: Doomsday,” Doom rapped about death directly, and heavily. But, even when he didn’t, the clouds still hung low above him. Listening to the album was like standing outside in a summer rainstorm. You felt drenched, drained, gut punched, short of breath. The album served as a multilayered memorial — an act of grief for a lost loved one, a somber tribute to an approach to music that was becoming extinct, and an unassuming yet towering act of artistic recalcitrance.

On “Operation: Doomsday,” Doom — whose October death was announced on New Year’s Eve — molded an approach to rapping and producing that was suffused with memory. His vocals were slurred, almost dreamlike. He could sound like he was rambling, which belied his rather astonishing sense of craft. In an era in which hip-hop was polishing its rough spots for mainstream acceptance, Doom was almost completely interior — he sounded like he was rapping to himself. The music was intimately, almost quixotically, personal.

Most crucially, though, Doom produced almost all of the music on “Operation: Doomsday”; he was a bedroom auteur before it became the norm. His sonic choices were radical — both no-fi and elegant, lush with history and emotion. He used familiar sappy songs as reference and foundation — Quincy Jones and James Ingram’s “One Hundred Ways” on “Rhymes Like Dimes,” the S.O.S. Band’s “The Finest” on his track of the same title — and built beats around them that felt like they were woven into the sample material itself. Sometimes he had specific older songs resung with slightly altered lyrics — Sade’s “Kiss of Life” on “Doomsday,” Atlantic Starr’s “Always” on “Dead Bent” — in a way that felt fully inhabited.

This approach was a conceptual innovation beyond a simple sample or interpolation. It suggested that you could not so much reinterpret or borrow from history as become one with it, experience and memory all bleeding together into something that wasn’t quite present or past, but some ineffable other thing.

That made “Operation: Doomsday” one of the most idiosyncratic hip-hop albums of the 1990s, and one of the defining documents of the independent hip-hop explosion of that decade. It was seismic in the true sense — a shift in terrain that exposed a fault line that had been developing for a while, and revealed a whole other realm of creative possibility, an opportunity for an alternate history.

It’s not that Doom — who first found success at the dawn of the 1990s under the name Zev Love X as part of the Native Tongues-adjacent group KMD — was working from a radically different playbook from those in the mainstream, many of whom were his generational peers. They, too, were making new music resting on the hits of yesteryear. But theirs was glazed; Doom’s was stewed. While mainstream hip-hop was optimizing itself for an impending pop takeover, here was someone who had opted out, some combination of refusenik and mourner.

All of this made him a hero to the heartbroken. Central to the narrative and myth of “Operation: Doomsday” — which was released on the foundational independent label Fondle ’Em following a string of 12” singles — was the creation of the supervillain character, MF Doom. Naturally, this supervillain, like all the others, had a tragic origin story: the death of his brother, the subversion of the genre he loved, the primal urge to continue making music outside of the system that had sustained him and then spit him out. (In 1993, a few months after Subroc’s death, KMD was dropped from Elektra Records before its second album, “Black Bastards,” was to be released, because of a controversy over the cover art.)

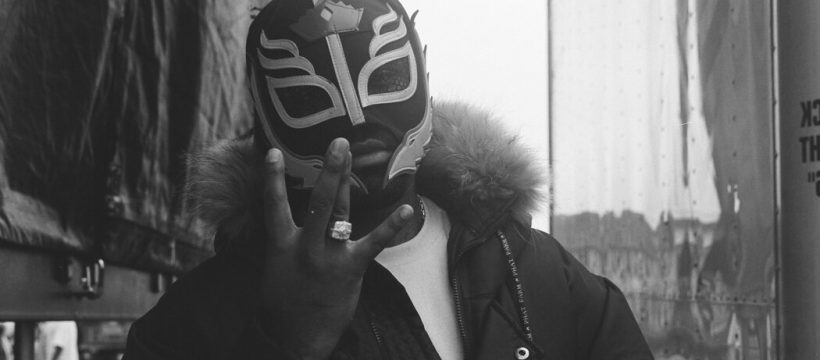

Hence, the mask. In the early Doom years, he tried out different versions — the one worn by the WWE wrestler Kane, a Mexican wrestling one, a torn stocking around the face — before landing on the one that became his signature.

They all served the same purpose, though. “I wanted to get onstage and orate, without people thinking about the normal things people think about,” he told The New Yorker in 2009. “A visual always brings a first impression. But if there’s going to be a first impression I might as well use it to control the story.” The mask was the lie that protected the truth.

Doom became a prankster, too, or at least an exorbitantly reluctant famous person. He would, from time to time, send others in his place to concerts, or photo shoots, sporting the Metal Face mask in his stead. It was a way to continue to de-emphasize the commodified self, to retreat even further into the sound. It allowed him to exist in the world as a memory, long before he left it.

Source: Read Full Article