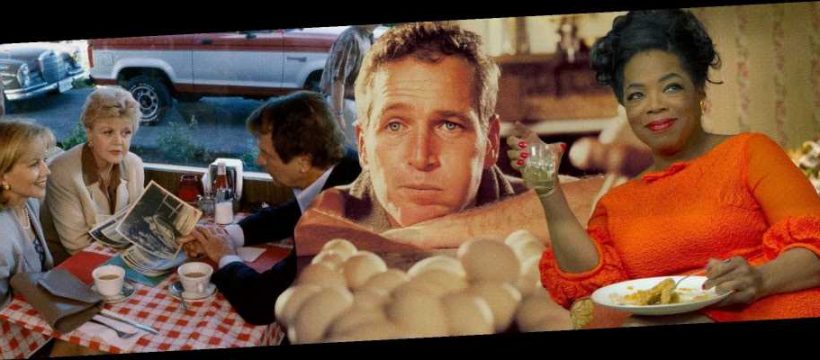

Do you ever notice the way actors eat on-screen? I do. Take the volatile dinner scene in “American Beauty.” It lasts three minutes, but we only see one bite of food enter someone’s mouth; the rest is just a lot of argumentative fork-waving. After the central family in Spike Lee’s “Crooklyn” blesses their supper, they spend a lot more time discussing the meal than actively consuming it. The Thanksgiving comedy “Home for the Holidays” used 64 turkeys, according to director Jodie Foster, but not a single one got eaten. And though Paul Newman downing 50 hard-boiled eggs in “Cool Hand Luke” is one of cinema’s most stomach-churning moments, the frenzy is pure wizardry: “I never swallowed an egg — the magic of film,” Newman told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch in 1993.

Maybe I should have posed a different question. Do you ever notice the way actors don’t eat on-screen? The creative lengths they go to avoid chewing in front of the camera, even if food is essential to the scenery? The sly editing that cuts away right before a spoon meets a mouth?

“Angela Lansbury taught me and I share it with other actors: She would always start with her fork in her mouth and take it out and pretend to chew,” said veteran food stylist Nancy Goodman Iland, who worked on the last few seasons of “Murder, She Wrote.” Actors need to speak intelligibly, and shooting multiple takes of the same scene requires them to limit their intake and maintain continuity. Start observing food closely and you’ll see what I mean. “You know, I don’t really eat on set,” Diane Keaton recently told Vulture.

Of course, sometimes an actor has to gobble it up ― picture Bill Murray hoisting an entire slab of cake past his chompers in “Groundhog Day” or the gobs of syrupy spaghetti that Will Ferrell inhales in “Elf.” That demands some very different strategies (more on that less appetizing revelation later).

In making all the food movie magic, modern actors are added by the food stylist, an unsung position that has become fairly ubiquitous in Hollywood over the past couple of decades.

Food stylists have mastered a number of ways to approach their complex workloads, which include researching, purchasing and preparing the food necessary for any given project and arranging said food so it photographs well take after take after take. Curious about their process, I talked to a number of stylists who help bring these tasty scenes to life.

“Food on film is the most temperamental actor,” said Christine Tobin, a Boston-based stylist whose credits include “American Hustle,” “Ghostbusters” and 2019’s “Little Women,” in which a savory Christmas banquet is the plot point that propels the March sisters’ neighborly romances.

Before they can start cooking, stylists must find out what actors are willing to eat. The several I spoke to agreed that most stars, however powerful, are only as exacting as they have to be when it comes to food. “Lee Daniels’ The Butler” stylist Richard Papier assumed someone as famous as Oprah Winfrey or Jane Fonda would have many stipulations, but neither had any. Susan Spungen said that Julia Roberts requested asparagus for a lunch scene in “Eat Pray Love” because it was easy to stomach. And sometimes actors are downright playful, like Brad Pitt, who told “Ocean’s Eleven” stylist Valerie Aikman-Smith that he’d prefer sweets while playing a slick crook routinely dining on the go — hence Pitt’s lollipops and ice cream.

And yet actors in general, stylists agreed, are still a lot more exacting now than they were before “gluten-free” and “paleo” became part of our everyday lexicon. When Melissa McSorley started out on series like “Freaks and Geeks” and “The Bernie Mac Show,” if performers were vegetarian, they’d simply avoid the meat on their plate. But with more food stylists on sets comes the expectation that everyone’s predilections will be accommodated.

That coordination is nothing compared to the detailed process that follows: creating a culinary composition in sync with the story’s aesthetics, tone and production schedule. Part of that equation is the meticulousness of the director in question. David Fincher and Nancy Meyers, for example, are known for doing dozens of takes, so if there’s food involved, the actors will need a lot of it. “Basically, your job is to plan a menu for every week,” said Papier, a New Orleans chef who took on movie gigs in the early 2010s when Louisiana was offering some of the best entertainment tax credits in the country.

That might mean hunkering down in a library to research old menus, like McSorley did when she was tasked with making every detail on “Mad Men” historically accurate. (Sample investigation: Was red velvet cake a thing during the 1960s?) Or it could mean inventing something fantastical, like McSorley did when she fashioned an enchanted LED apple native to a fairy wonderland for HBO’s “True Blood.”

Unlike home cooks, the food stylist must prioritize appearance over taste, which leads to all sorts of tricks we’re not meant to notice. Papier discovered that adding Elmer’s glue to a glass of milk prevented it from developing a blueish tint on-camera. Others have grabbed spray bottles to maintain that oven-fresh glisten or tweezers to refine the microscopic details of how some delicacy is arranged on a plate. (No wonder actors shy away from actually eating the food in front of them.) On “Julie & Julia,” Spungen took matters into her own hands, literally: “Now, you really think that Meryl Streep is going to stand there for hours lacing up a duck when it’s not necessary?” she said. “It’s the same thing as having a body double for sex scenes. You don’t want to have to have the actor on set if they don’t need to be.”

Before alleged “Matilda” thief Bruce Bogtrotter (Jimmy Karz) could cram down an obscene amount of chocolate cake as punishment, prop master Emily Ferry had to find a baker who could fashion a three-layer confection that was sufficiently messy but didn’t resemble “a giant pile of excrement.” Ferry ordered numerous versions, testing the size, color and filling. She also commissioned styrofoam replicas because the real cakes were too heavy for the actors to carry.

“We shot that for weeks,” Ferry recalled. “There are laws in California as to how many hours a child can work, and also, poor Jimmy, he could only do that for so long before he started getting green around the gills. So we would shoot for a while and then we would come back to it. And we would have to call the poor baker in Long Beach and say, ‘We need another six cakes.’ And finally, towards the end of it, she was going, ‘Oh no, not another one.’”

If you were to watch the raw footage, Ferry said, you’d see a props person scurrying around between takes to hand Karz a spit bucket — a receptacle common in scenes that demand heavy consumption. Kate Winslet used one while making the 2013 melodrama “Labor Day,” in which she had to eat “scone after scone after scone,” Tobin said. Even nonfiction programming uses spit buckets, as Spungen saw while working on an episode of PBS’s “American Experience” about Industrial Revolution-era food manufacturing.

All of this is to say that food stylists have one of the most interesting jobs in Hollywood. It’s only going to get more complicated in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2020, McSorley participated in an industry-wide committee dedicated to determining new safety protocols. While the virus isn’t known to be transmitted via food, stylists still need to shield their equipment.

“You have to be a very specific personality to be a food stylist, I will tell you that,” said Goodman Iland, the “Murder, She Wrote” stylist whose other credits include “The Good Place,” “A Star Is Born” and “Straight Outta Compton.” “That means that you have to be ready to show up, rush, set up, get it done, and then sit down and wait for hours. Or you might show up and wait for hours, and then rush and get it together. And it might be that you are given some wild food scenes, and you have to figure out how to do it and how to make it work.”

RELATED…

Related

Trending

Source: Read Full Article