The same five binders have traveled with Anya Davis for more than 20 years as she moved from Pennsylvania to Virginia to North Carolina. In them are personal records of her mother’s celebrated dance career and experiences in the early years of New York City Ballet. Back in 2000, when Davis and her mother, Patricia Wilde, a former City Ballet principal, first began to look through the boxes Wilde had been storing in her home in Pittsburgh, they spent half a year carefully sorting through the photographs and playbills, and enjoying the stories Wilde had packed away along with them.

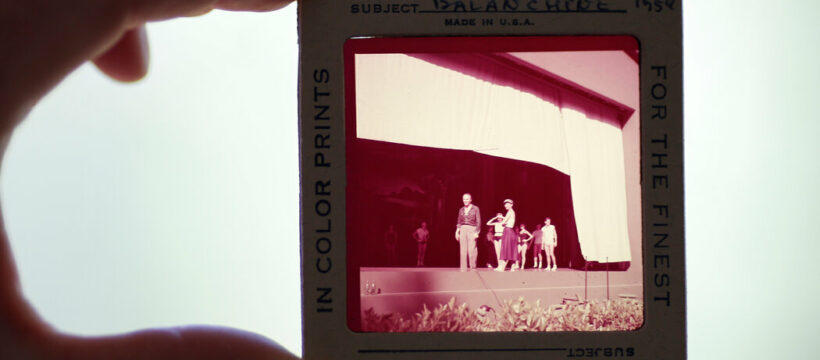

One of the densely filled boxes had slides of visits to the Connecticut cottage that George Balanchine, the co-founder of City Ballet, shared with the ballerina Tanaquil Le Clercq, who was then his wife — like an image of Wilde and Le Clercq lounging together in comfy slippers, smiling at the camera while flipping through newspapers. In another box were letters from dancers like Edward Villella, and an old tour itinerary: 21 cities in 25 days, by train. All were put into binders, chronologically when possible.

Davis has devotedly taken care of these binders and scrapbooks over the years, she said, as we paged through a few in a quiet booth at a New York diner. Davis had brought a manageable selection of photographs and correspondence for us to view together on a recent visit to the city. It was not quite half the collection, but it still took up much of her car’s trunk.

Soon all the items, donated by Davis, will head to the Jerome Robbins Dance Division at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts. That was what she had discussed with Wilde, who died in 2021 at 93. Davis will keep a few things, including a picture of Wilde in class with Balanchine. “I knew it was her absolute favorite,” she said.

Dancers and choreographers often become unintentional collectors, accumulating valuable records of an art form with few tangible traces. And once artists are gone, families are left to be caretakers of dance history. They may be tasked with identifying obscure photographs and deciphering faded handwritten letters while keeping them safe from leaky attics and the ravages of time.

For a lucky few, like Davis, those family treasures will find an enduring home of protection and care — in an archive.

“It’s your voice across time,” said Linda Murray, the curator for the Jerome Robbins Dance Division, one of the most extensive dance archives. “When you’re no longer around to speak for yourself, and when everybody who ever knew you and ever saw you dance is no longer around to talk about your contributions, the objects that you place in your archive are going to be the things that tell that story on your behalf.”

Storing these items requires space and resources, so archives must carefully consider what they collect and why. The Dance Division at the New York Public Library receives more inquiries than it can accommodate. Murray said she looks for materials that will add layers of information to the library’s holdings, always adapting to the unpredictable nature of when these personal files may become available.

For the library, acquiring Wilde’s collection is a way to enhance existing materials about artists who worked directly with Balanchine. He created several roles for her, including in “Square Dance” (1957), a celebration of the exhilarating precision and fireworks that Wilde brought to the company.

“How can you say no to Patricia Wilde?” Murray said. “She’s a Balanchine ballerina, she was one of the original interpreters of much of his choreography, and also a beloved teacher to subsequent generations of dancers.”

In 2021, Murray acquired the collection of Ruth Ann Koesun, an Asian American ballerina and principal dancer with American Ballet Theater from the late 1940s through the ’60s. Koesun’s materials contributed an essential perspective to the Dance Division’s holdings. “I think we don’t have enough representation for Asian American dancers in the field of ballet, and Ruth Ann was an innovator in that area,” Murray said. “Even within the dance field, I don’t think her name is as well known as it should be.”

Koesun was a creative force in a range of roles, including the revival of “Billy the Kid,” which she performed in 1962 at the White House for the Kennedys. She kept the costume she wore neatly packed away.

When Koesun died, in 2018, she left her archive to her goddaughter Ellen Coghlan with instructions to donate it, and Koesun’s hope was that it would end up at the Dance Division. There was no backup plan. So Coghlan and her husband began the intensive job of cataloging everything Koesun had saved, including her first contract with Ballet Theater, co-signed by her mother because she was only 17.

Boxes took over nearly every room of their home, Coghlan said, as they paged through Koesun’s personal letters from tours, photographs, press, and copies of an issue of Life magazine from 1947, when she appeared on the cover with the ballerina Melissa Hayden.

“It was a big responsibility because she was alone,” Coghlan said of Koesun. “So when she passed away we were in charge of all her stuff, which is more than any normal person has, but she was family.”

Some families search for years, and even decades, to find an ideal home for their loved one’s possessions, if they find one at all. And while these collections are crucial sources of discovery for researchers, they can also be eye-opening for the family members.

Primavera Boman inherited the London home of her mother, Hilde Holger, more than 20 years ago and looking at each item has been revelatory. “I’m learning who my family is,” Boman said.

Boman had known that her mother was a prominent expressionist dancer and choreographer in Vienna, Bombay and London. But she didn’t know the extent of Holger’s influential dance career, first performing with Gertrud Bodenwieser’s dance group, and then with her own touring company, Hilde Holger Tanzgruppe, all before World War II.

“I had no idea that my mother was so well known in Vienna before Hitler came,” Boman said. “I’m becoming like a historian, a conservationist, an archivist.”

After years of trying, though, Boman still hasn’t placed the collection. She has done the sorting and the cataloging, and maintains a detailed inventory of every sketch and letter, ready for the opportunity to make her donation. Even in cases when an archive readily expresses interest, that initial work is mainly the family’s responsibility, and it requires endurance.

Léo Holder, the son of the artist, dancer and choreographer Geoffrey Holder and the dancer Carmen de Lavallade, 92, said that when Holder died in 2014 some of the stored items hadn’t been seen in 30 years. “They lived in a 5,000-square-foot loft,” Léo said of his parents. “By the time we moved out of that loft, there was maybe 500 square feet of walking space left.”

Until then, he hadn’t realized the scope of the materials. “It’s movie history, it’s Black history, it’s Black theater history,” he said. “It’s more than just one thing.”

Geoffrey Holder, who met de Lavallade when they both appeared in the 1954 Broadway production of “House of Flowers,” saved everything: not just items related to their significant and extensive careers, but also the stuff of their lives. He filled Ziploc bags and traveling trunks with bills and greeting cards, as well as treasures like footage from “The Wiz” (1975), which won him Tony Awards for direction and costume design; and a frail costume nestled in a suitcase from de Lavallade’s 1962 tour of Southeast Asia with Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, during which she performed alongside Ailey, even appearing on promotional posters as “The de Lavallade-Ailey American Dance Company.”

Léo had offers to place his parents’ collection with other institutions, but his decision to work with Emory University came down to the connection he felt with its head curator. Now the collection is kept at Emory, in Atlanta, in the Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library as the Geoffrey Holder and Carmen de Lavallade Papers and numbers some 280 boxes with content spanning the years 1900 to 2018.

“This put me through my paces,” Léo said, recalling the sorting, which took him two years. “Sifting through every little thing, and finding gems all the time.”

The emotional element connected to these donations is not one that is always considered. Murray noted that when a donation comes from a family rather than a trust or an estate, it can become intertwined with the grieving process — there is a catharsis in letting go when the time is right.

Davis is preparing the Patricia Wilde collection for its send-off, and there is much affection in her familiarity with each photo. At the diner, Davis reached across the table and pointed to an image of her mother in Balanchine’s “Pas de Dix.” Wilde gazes directly at the camera, hands beneath her chin, her eyes and tiara shimmering in the studio lights. “I love this one of her,” Davis said. “She looks like she’s blowing us a kiss.”

Family members have kept anything meaningful to them, Davis said, because once the collection is signed over to the library there is no special access granted. “Choose, and choose wisely,” she told her nephews.

The calm that follows these significant donations is something Léo seems to know all about. “It was on my shoulders, and I’m just one person with all the information,” he said. “It was keeping me up at night. The thought of it being someplace where it is safe, I couldn’t be happier.”

Source: Read Full Article