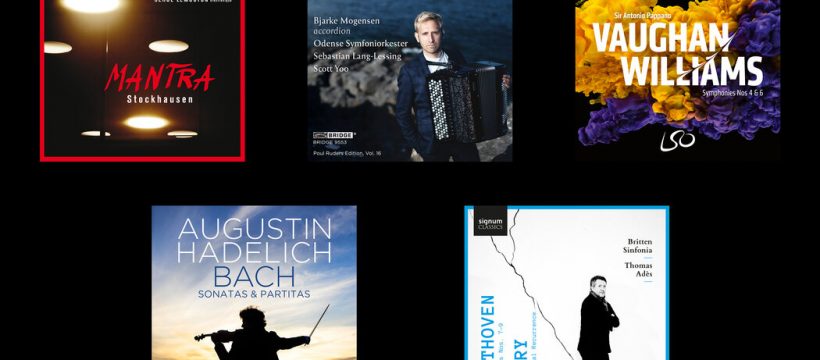

Bach: Sonatas and Partitas

Augustin Hadelich, violin (Warner Classics)

Bach, it seems, has been the composer of the pandemic, his music speaking to many of the full spectrum of human experiences and emotions. Isolated musicians, too, have pulled out their scores of his solo works — miracles of making symphonies out of single instruments.

Count the violinist Augustin Hadelich among them. He devoted much of 2020 to Bach, eventually fulfilling a long-held dream of recording the monumental sonatas and partitas. It’s a risky endeavor, with the challenge of standing out in an overcrowded field.

Hadelich succeeds, generally, with a technically assured interpretation that is devoted neither to historically informed performance nor to the old-fashioned style of a Jascha Heifetz. Playing with a Baroque bow, Hadelich’s sound is crisp and light, and flashes of vibrato are deployed judiciously, as in his graceful reading of the Second Sonata’s Andante and his achingly lyrical account of the Largo from the Third Sonata.

Elsewhere, the music reveals Hadelich’s gifts for shading — the great Chaconne from the Second Partita has stark contrasts here — but also betrays his shortcomings, particularly his unreliability in teasing out implied counterpoint. This album captures just a single moment in time, though — and for so many these works are a lifelong project. Let’s hope they are for Hadelich, too. JOSHUA BARONE

Beethoven and Gerald Barry: Symphonies and ‘The Eternal Recurrence’

Britten Sinfonia; Thomas Adès, conductor (Signum)

When a conductor is coming out with a cycle of Beethoven symphonies, it’s a bit like watching a pitcher approach a no-hitter; you don’t really want to jinx the proceedings by talking about it as it’s happening. But now that Thomas Adès’s account of the nine works, recorded with the Britten Sinfonia between 2017 and 2019, has finally been released, listeners can breathe easy.

In the final album of the series, renditions of the Seventh, Eighth and Ninth symphonies make familiar passages glint anew. Early on during the first movement of the Seventh, there is a convivial quality to the call-and-response between strings and winds, instead of rote volleying. This means that later on, when the full ensemble converges, there is a potent sense of collectivity — no matter the chamber-orchestra scale of these forces.

Throughout the cycle, Adès has paired Beethoven with the antic entertainments of the contemporary composer Gerald Barry. Here, these players’ account of Barry’s “The Eternal Recurrence” vibrates with the same joyous commitment to detail as in the symphonies. SETH COLTER WALLS

Poul Ruders: ‘Dream Catcher’

Odense Symphony Orchestra; Bjarke Mogensen, accordion; Sebastian Lang-Lessing and Scott Yoo, conductors (Bridge)

The Danish composer Poul Ruders has long written works that subtly blend ravishing sounds, abundant imagination — and intricate modernist technique. But, as he writes in the liner notes for this new recording of “Sound and Simplicity” (2018) for accordion and orchestra, four of the seven movements of this mysterious, volatile piece are “very simple” — that is, with an “absence of any structural and metric complexity.”

The second movement, “Trance,” is indeed simple: an eerie prolongation of a sustained chord of just four notes. But other sections of this 30-minute score are dark and frenetic, like “Wolf Moon.” Perhaps most captivating is the sheer range of strange, delicate and piercing sounds the brilliant Bjarke Mogensen draws from the accordion; who needs synthesizers when you have this virtuoso in your ensemble? On the album, Mogensen also plays his own solo arrangement of Ruders’s contemplative, harmonically tart “Dream Catcher,” whose theme is incorporated into Ruders’s Symphony No. 3, a 2012 recording of which is reissued here. ANTHONY TOMMASINI

Stockhausen: ‘Mantra’

Jean-François Heisser and Jean-Frédéric Neuburger, pianos; Serge Lemouton, electronics (Mirare)

Karlheinz Stockhausen’s “Mantra,” a two-piano epic written in 1970, seems like it wanders freely over its hourlong span. But it’s actually tightly constructed. At the start is a 13-note theme — what Stockhausen called a formula, or mantra — which is manipulated over the course of the piece.

This is not exactly a theme and variations, because the formula is barely varied; it’s just expanded and compressed, in speed and in pitch. Each of the 13 notes is associated with a certain quality — like crisp staccato, a trill or a certain accent emphasis — and over 13 sections, Stockhausen applies those qualities, one by one, to the treatment of the formula, culminating in a ferocious climactic toccata.

This can read as dry — purely conceptual. But the results have a seductively, shadowy nocturnal sensuality, especially since the sound from the pianos is processed by electronics, leading to a variety of effects: coppery shimmer, forlorn echo, loopy daze, tender cloudiness. The two pianists also play wood blocks and crotales (small tuned cymbals), and even briefly chant, for the kind of ritualistic mood that would be a major part of Stockhausen’s legacy for some composers in the 1970s and ’80s.

But this recording is notable for a performance, and particularly the use of the electronics, that doesn’t feel dated or mired in late-60s psychedelia. For this, and for their generally precise, evocative work, the pianists Jean-François Heisser and Jean-Frédéric Neuburger, the electronics artist Serge Lemouton and the record label, Mirare, deserve great credit. ZACHARY WOOLFE

Vaughan Williams: Symphonies No. 4 and 6

London Symphony Orchestra; Antonio Pappano, conductor (LSO Live)

Simon Rattle shocked the music world in January when he announced he would leave the podium of the London Symphony Orchestra for the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra in Munich. Two months later, even an ocean away, you could hear the sighs of relief when Antonio Pappano was named his successor.

Few conductors are held in higher esteem in Britain — or anywhere — than Pappano, the longest-serving music director in the history of the Royal Opera. And though there are legitimate questions about where a conductor mostly known for his work in the opera pit might take an orchestra of such prestige and inquisitiveness, the fit is promising between ensemble and local (Essex-born) maestro, especially at a time when Brexit and Covid-19 have destabilized British culture and the country’s sense of itself.

As if to highlight that point, along comes this release: a live taping of concerts from 2019 and just before the 2020 lockdown that is easily Pappano’s most impressive symphonic recording. Vaughan Williams’s Sixth is difficult and ambivalent, but Pappano tears into it, forcing it upon you to tremendous effect. And the wartime Fourth hasn’t received a recording this blazing, ferocious and convincing since Leonard Bernstein’s with the New York Philharmonic, half a century ago. It’s stupendous stuff, and only, one hopes, to be bettered in the years to come. DAVID ALLEN

Source: Read Full Article