FAMILIES looking to plan a staycation in 2024 without spending a fortune might want to take advantage of these new budget-friendly deals. Haven has released

FAMILIES looking to plan a staycation in 2024 without spending a fortune might want to take advantage of these new budget-friendly deals. Haven has released

Former Love Islander and Made in Chelsea alumni Zara McDermott is not one to hold back when it comes to sharing her beauty secrets, which

The typical adult starts thinking about their own funeral at the age of 51, according to a study. Research, of 2,000 people, found the most

Mariah Carey and her longtime boyfriend Bryan Tanaka have decided to go their separate ways after seven years together due to Bryan wanting children, it

South Park is rounding out the year with an OnlyFans special, “Not Suitable for Children. Now available to watch on Paramount+, the trailer released shows

I was sacked after 20 years as a teacher for standing up to gender ideology. The new guidance is welcome – but we must go

Steven Harrington recently announced his first ever museum solo exhibition that will take place next year at Seoul’s Amorepacific. In another first, the Los Angeles-based

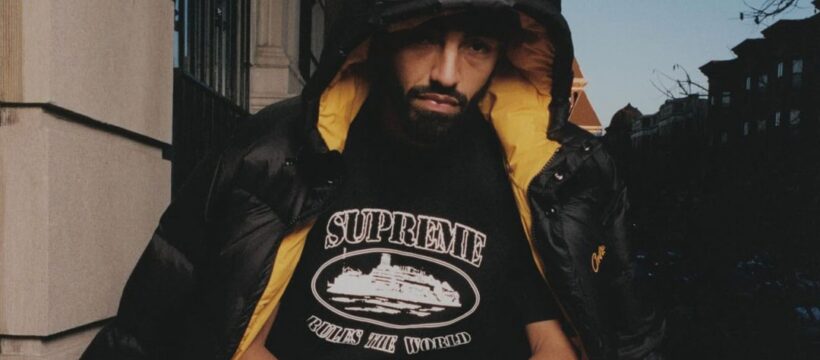

After teasing a Supreme collaboration with a co-branded billboard in London earlier this week, British streetwear imprint Corteiz has taken to social media to offer

Chicago-based visual artist Louis De Guzman has been fleshing out his Along The Way universe throughout the year, delivering paintings, sculptures and merchandise that exist

This Morning's Josie Gibson has revealed her plans to spend Christmas at luxury £500 a night Welsh hotel after her stint on I’m A Celebrity…Get

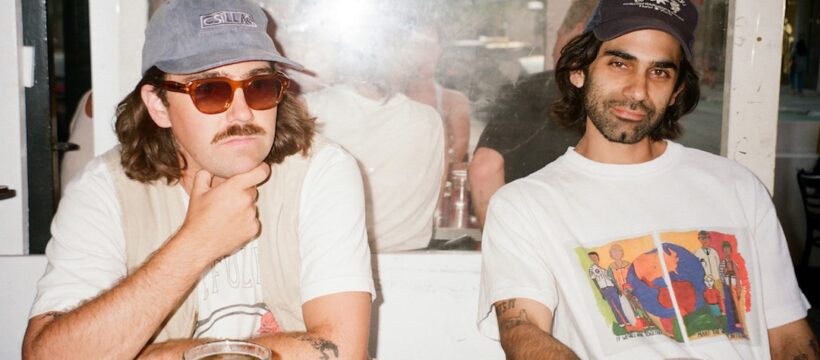

This article originally appeared in ‘Hypebeast Magazine Issue 32: The Fever Issue.’ Please visit HBX to grab your copy. In another life, Nick Williams and

Jonathan Majors has fled the Big Apple after his high-profile guilty verdict — he’s in Los Angeles, and he’s still rolling with his ever-loyal GF

Legendary punk bands Bad Religion and Social Distortion have announced a co-headlining 2024 U.S. tour. The trek will see Social Distortion performing their classic debut

Shirley Ballas Says Ellie Leach Isn’t Leaving Without The Trophy Strictly Come Dancing finalists Layton Williams and Bobby Brazier put on equally incredible performances but

Over the weekend at the Jump Festa’ 24 event, TOHO Animation shared the latest promotional trailer for Kaiju No. 8, the upcoming TV anime based

IF you follow Ferne McCann on social media, it won’t take too long to realise that she has a very lavish lifestyle. But it’s not

NOW the weather is truly ready for Christmas, we’re all looking for ways to keep ourselves warm without adding to our heating bill. And Dunelm

GETTING a bottle of Baileys in for Christmas (or several) is top of the shopping list in many households this festive season, including my own.

Save articles for later Add articles to your saved list and come back to them any time. Prime Minister Anthony Albanese has suggested Australia will

Houseplants that are ‘impossible to kill’ Chris Bonnett from GardeningExpress.co.uk said: “Condensation is a common problem throughout the winter months but too much can be

South Park is rounding out the year with an OnlyFans special, “Not Suitable for Children.

Read more

FAMILIES looking to plan a staycation in 2024 without spending a fortune might want to

Read more

Houseplants that are ‘impossible to kill’ Chris Bonnett from GardeningExpress.co.uk said: “Condensation is a common

Read more

Many people cook the spuds on the day they plan to tuck into a roast

Read more